Philosophy

Page under development - with thanks to Victor

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is the application of the faculty of thought to main aspects and questions related to the human worldview of how Man stands in the world and cosmos. It applies thought in a systematic way to the study of universal questions regarding existence, reason, knowledge, and ethics; thereby also focusing on the process and critical method of inquiry and rational logical reasoning.

The scope of philosophy explores, in different branches, questions such as

- how do we know what we know? (epistemology),

- how do we build and develop knowledge and understanding? (logic),

- how do we humans make choices and what are the implications of morality? on society ,and for humanity as a whole (incl. problem of good and evil) (ethics), and:

- what is our place in the cosmos and the meaning of our existence? (metaphysics).

Other branches apply also to art and beauty, science and the scientific method, language (meaning of words and concepts), politics and societal organization.

As philosophy relates to the faculty of thought, philosophy evolved as the human consciousness developed across millenia.

Philosophy therefore needs to be seen as directly related to the Development of the I, as it is the Human 'I' that provides the faculty of thinking. The changes across the last cultural ages is sketched through the description of the different nature of the threefold human soul, see Schema FMC00.431 on Human character - the I and threefold soul.

Human history of philosophy starts with the Ancient Greek philosophers in the third Greco-Latin cultural age of the intellectual soul.

The change in consciousness in the Current fifth cultural age of the consciousness soul brought, brings and will bring changes in the worldview due to the slow advent of new faculty of clairvoyance.

In that context Rudolf Steiner - building on the work of Aristotle, Goethe, Fichte and Hegel - focuses on the epistemology of spiritual science and the spiritual scientific worldview based on the concept of free thinking, thinking that goes beyond the thinking about physical-mineral reality, objects and concepts with waking consciousness. See 'creation of free thought' on Schema FMC00.490 below.

Note this page contains both general quotes that provide significant insights, as quotes that succinctly characterize a reference to a work or an author.

Aspects

- seven branches of philosophy:

- Epistemology (knowledge), Ethics (morality), Logic (reasoning), Metaphysics (reality), Aesthetics (beauty), Political Philosophy (government), and Philosophy of Science (science methods)

- four main or central

- Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that studies the source, nature and validity of knowledge.

- Ethics – study of value and morality, what are moral principles and what constitutes right conduct.

- Logic – the systematic study of the form of valid inference and reasoning.

- Metaphysics – concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it (ontology, cosmology, time and space)

- methods to arrive at philosophical knowledge: description of experience, conceptual analysis, critical questioning, logical reasoning (inference, induction, deduction), use of thought experiments, positioning elements of common sense and intuitions.

- The way how Man has approached these themes is universal but still embedded in culture, with difference in perspective eg between Chinese, Arabic, Indian, or Western philosophy. In all branches there are many competing schools of thought supporting and promoting different principles, theories, and methods.

Kant <-> Hegel

- two philosophies underlying a schism in worldview, including the human being and observer in the process or not

various

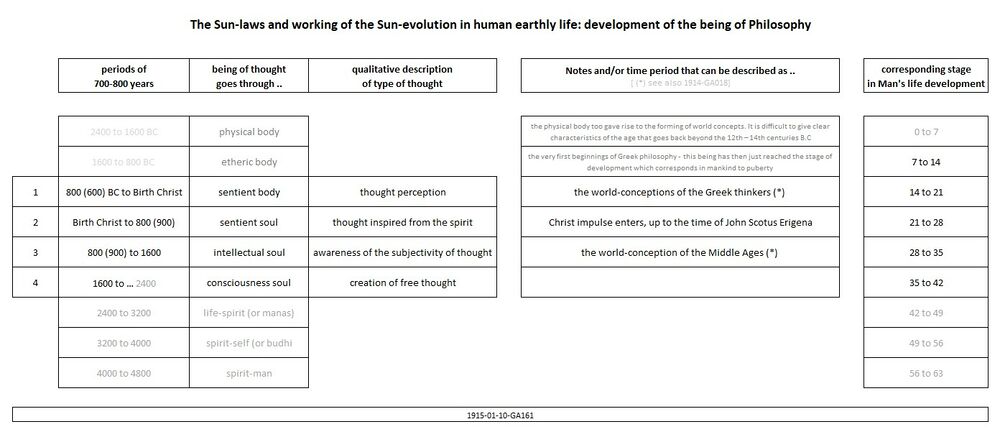

- the working of the sun-laws or the working of the Sun-evolution in human earthly life) can be found in the study of the course of philosophical evolution. Eight-hundred year periods can be distinguished in the development of philosophy (1915-01-10-GA161) - see Schema FMC00.490.

- relation of philosophy to cosmology and religion (1922-09-GA215)

- furthermore also see:

- terminology:

- teleology, cosmogony, eschatology, entelechy; see topic page Meaning of life (should probably me moved from Discussion Notes )

- Man's most important questions

- terminology:

- twelve worldviews and philosophers (see also Schema FMC00.648A right)

- phenomenology: Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (1859-1938)

- monadism: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) eg with 'Monadology' (1714); Christian Wolff (1679–1754) - follower of Leibniz who systematized and expanded monadology and helped spread monadism through academic circles in Germany.

- sensualism: Étienne Bonnot de Condillac (1714–1780) eg with 'Treatise on Sensations' (1754); John Locke (1632–1704); David Hume (1711–1776) eg with 'A Treatise of Human Nature' (1739–1740)

philosophers

This section is to provide key works

Fourth Greco-Latin cultural age

- Lao Tzu

- Confucius

- Socrates

- Plato

- Aristotle

- Aquinas

- neo-platonism: Plotinus, Lamblichus, Porphyry

Current fifth cultural age

- Descartes

- Locke

- Baruch (de) Spinoza (1632-1677)

- Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

- Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814)

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900)

- Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900)

- Franz Brentano

- Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925)

- see also: The life of Rudolf Steiner and Individuality of Rudolf Steiner

- 'Philosophy of Freedom' (all related quotes on the same page with other references; the paragraph at the top of the page could simply say a sentence about its importance)

- Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889 - 1951)

- Heidegger

- furthermore on this site: on the Karmic relationships topic page: Schema FMC00.497 and Schema FMC00.243A

Inspirational quotes

J.G Fichte quoted by Rudolf Steiner in his introduction to G007 'Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age'

It would be easier to get most people to consider themselves to be a piece of lava in the moon than a self. He who is not in agreement with himself about this understands no thoroughgoing philosophy and needs none. Nature, whose machine he is, will lead him without his doing anything in all the acts he has to perform.

In order to philosophize one needs independence, and this one can only give to oneself.

We should not want to see without eyes, but we should also not affirm that it is the eye which sees.

Illustrations

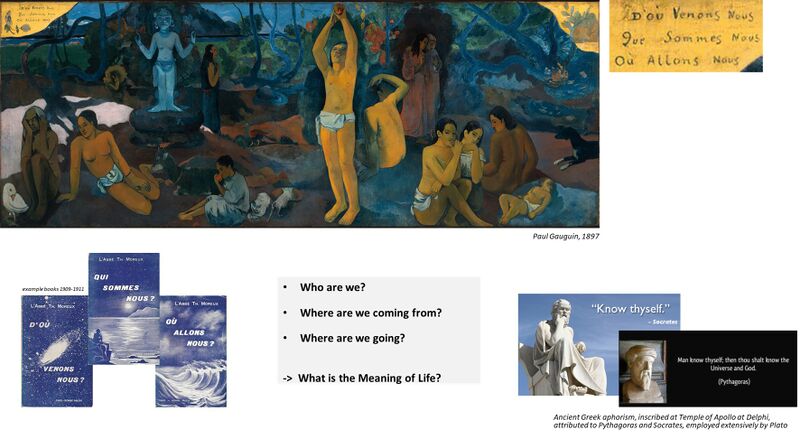

Schema FMC00.037 illustrates Man's most important questions in the conscious quest for the meaning of life.

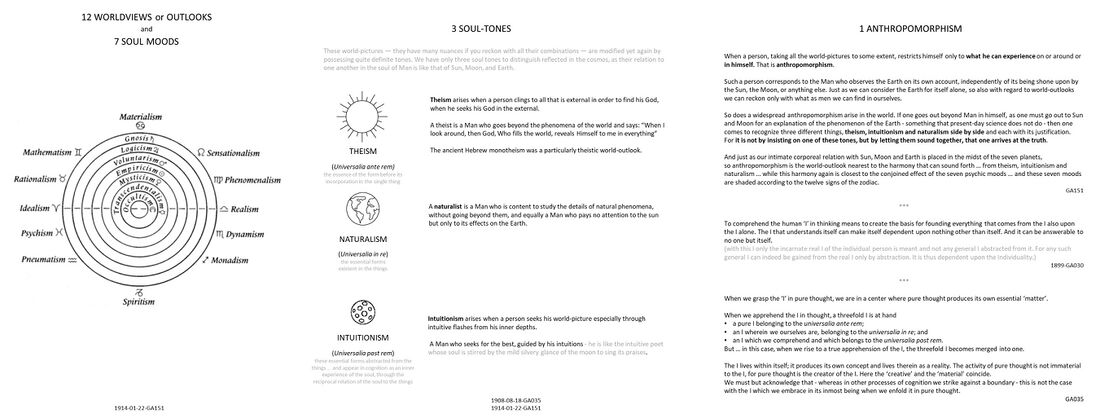

Schema FMC00.648: Twelve worldviews, seven soul moods, three soul tones, one anthropomorphism.

The world discloses itself only to someone who knows that one must look at it from all sides. The schema is structured around the 1914-GA151 four lecture cycle, in which all possible worldviews are decomposed into the exhaustive 12+7+3 set of elementary conceptions, whose already existing combinations make up the history of Western philosophy, and yet unrealized combinations its future potentialities. While the matter is framed philosophically, the schema is valid for any human being capable of developing a worldview. The lecture cycle suggests the possibility of thinking about worldviews dynamically. For descriptions and examples, see Schema FMC00.648A.

Despite the brevity with which the cycle addresses the right part of the schema — the so-called anthropomorphism — it is more difficult than the previous parts; and careful study of the references is recommended, as even the term itself could be misleading if understood habitually.

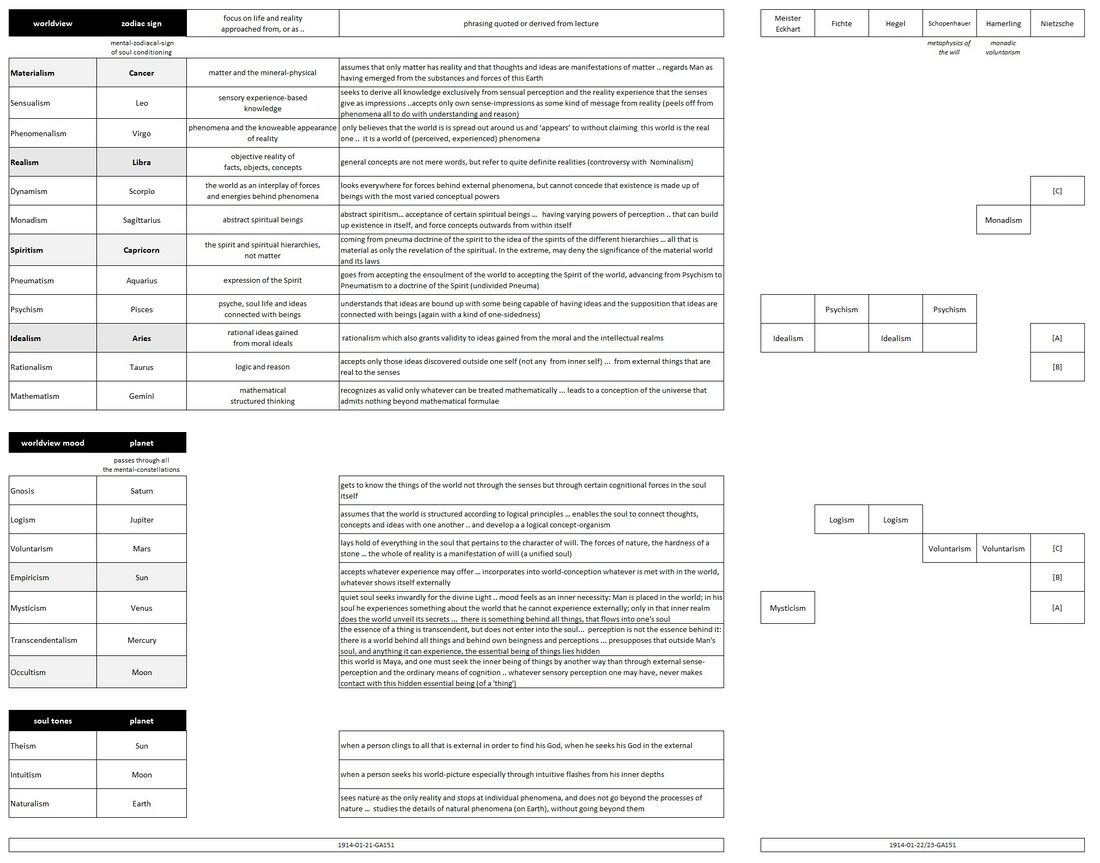

Schema FMC00.648A: provides a tabular overview with descriptions of the twelve worldviews and seven soul moods given by Rudolf Steiner, along with examples on the right.

All twelve perspectives or conceptions of the world are equally and fully justifiable .. and each may act illuminating in its own field. It is possible for the human soul to pass through a mental circle which embraces twelve world-pictures. Also for each worldview different soul moods are possible.

The four highlighted worldviews provide an X-Y axis materialism-spirit(ual)ism (Y) and idealism-realism (X), see Schema FMC00.648, whereby people with perspectives above the X-axis are typically more rigid or stubborn and those below the X-axis more flexible to switch or adopt another view.

Rudolf Steiner gives the example of Nietzsche to show one should use this framework rigidly to 'box in' philosophers or scientists, as one's soul evolves throughout life also (as in his example from A to C).

Schema FMC00.490 shows how the human thought about Man and the cosmos, or philosophy, evolves in periods of approx. 800 years related to the sun laws.

Note everything in light grey - the extensions after 2400 and the time periods before 800 BC were added by extrapolation and are not covered in the lecture.

Compare with Schema FMC00.376 and variants and Christ Module 11 - A new physics

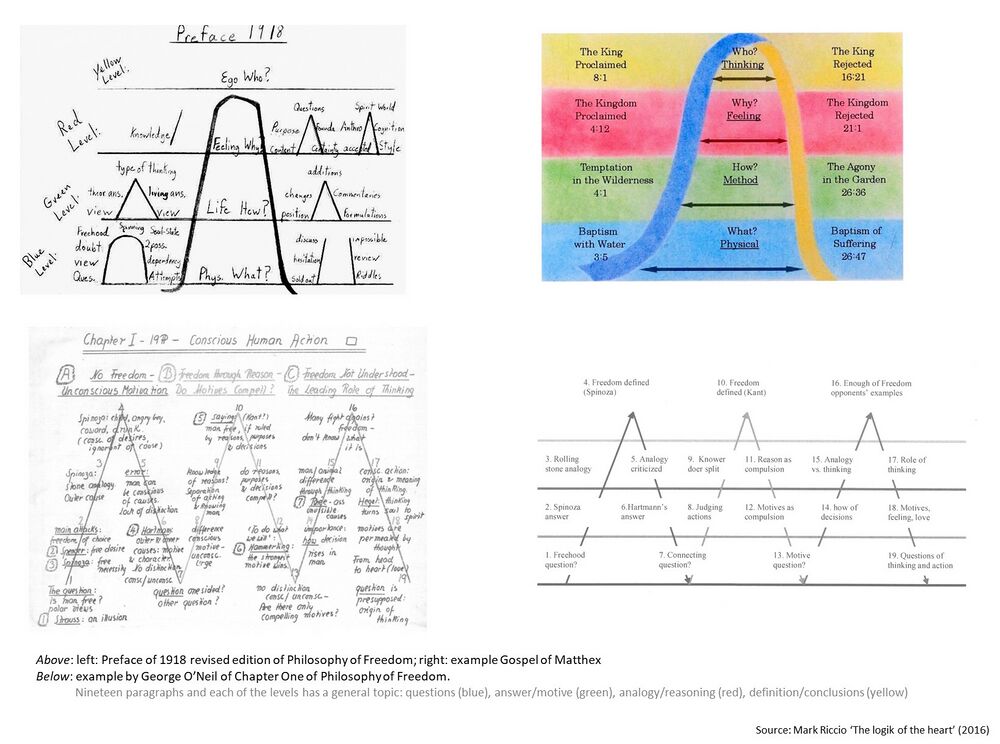

Schema FMC00.585: shows a few illustrations to show the organic structure that was discovered by George O'Neil in Rudolf Steiner's books, taken from Mark Riccio's book 'The logik of the heart' (2016). As described in the book, Rudolf Steiner composed his books, chapters and sentences in organic forms resembling musical notation. Implicit are the four organic laws of metamorphosis: rhythm, enhancement, polarity and inversion. The work done by George O'Neil and his students Florin Lowndes and Mark Riccio (and their work groups) has shown that practicing this study technique can transform one's faculty of thinking, exactly as Rudolf Steiner had pointed out about the effect his work 'Philosophy of Freedom' could have. Quoting from the book: "At some point one sees the whole contents as an idea in the mind's eye as a living-painting-form." and " O'Neil suggest that at some point you can see through the text content, colors and forms, and perceive the thought beings behind a chapter. "

This appears to be one of anthroposophy's well-kept secrets, though Rudolf Steiner referred to it as "heart thinking" (1910-03-29-GA119), "living thinking" (1922-09-30-GA216, 1922-10-07-GA217) or "formative (or Goethean) thinking" (1919-01-01-GA187), "thinking, using the etheric body" (1919-06-12-GA193).

Lecture coverage and references

Philosophy and anthroposophy or spiritual science

1908-08-18-GA035

The article 'Philosophy and Anthroposophy' places anthroposophy in the context of philosophy and its history, concisely going over a series of crucial topics.

1922-03-07-GA081

1922-04-29-GA212

this short excerpt describes the start of the process of introspection

Man's experience when he begins to observe his inner life, when he engages in what is usually termed introspection, is of his concepts derived from sense perception, of will impulses that come to expression in external action and of memories of past events. He experiences this as something isolated within himself. However, a more penetrating insight into his own being will soon make it clear that this kind of self-observation does not satisfy the deeper needs of man's soul. In the depths of his innermost being he is obliged to ask:

What is that in me which belongs to something causative, perhaps to something eternal, and which lies at the heart of all the passing phenomena before me in Nature and in human life?

There is a tendency in man to seek, at first, the deeper reality of his being in feeling and sensation. This leads him to questions which arise out of his religious or scientific knowledge such as:

Where are the roots of my innermost being? Do they stem from an objective reality, a cosmic reality? Is perhaps their origin something which though external is yet akin to my innermost self? Is their nature such that they will satisfy the deepest needs of my soul to have originated from them?

A person's inner mood and attitude to life will depend upon whether he is able to find answers of one kind or another to these questions which are fraught with significance for his inner life.

These introductory remarks are meant to draw attention to the fact that man's soul life harbors a contradiction. This comes to expression, on the one hand, in his feeling of isolation within his thinking, feeling and willing, and, on the other, in that he feels dissatisfied with this situation. The feeling of dissatisfaction is enhanced through the fact that the body is seen to partake of the same destiny as other objects of nature in that it comes into being and again passes away. Furthermore, since to external observation the life of soul appears to dissolve when the life of the body is extinguished, it is not possible to ascertain to what extent, if at all, the soul partakes of something eternal.

General

Johannes Scotus Eriugena

Philosophy, the study of wisdom, is not one thing & religion another... What is the exercise of philosophy but the exposition of the rules of true religion ... by which the supreme & principal cause of all things, God, is worshipped with humility and rationally searched for?

1893-03-25-GA030

On the History of Philosophy

1908-10-26-GA244 - Q&A172.3

provides an excellent introduction to philosophy, positioning Thales, Pythagoras, Aristoteles, Plato, Heraclitus <-> Parmenides, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Fichte. Philosophy tries to express reality through material concepts, it is a technique of concepts.

Philosophical form only arose between the fourth and sixth centuries BC, building on the wisdom from the Mysteries which was so universal that there were contradictions. This in contrast as philosophers do argue, as a consequence of the limited or selective perspective taken on a more complex reality.

1915-01-10-GA161

see Schema FMC00.490 and extract on: Christ in the future cultural ages and next epochs#1915-01-10-GA161

1920-05-23-GA074

Albertus and Thomas say: If you look back when your soul reflects what it has experienced in the outside world, then you have the universals living in your soul. You then have universals. You form the concept of humanity from all the people you have met. After all, if you remembered only individual things, you could live merely in earthly names.

In that you do not at all live merely in earthly names, you must experience universals.

There you have universalia post res, those that live in the soul after the things.

While Man turns his soul towards things, he does not have the same in his soul as what he has afterwards when he remembers it, when it is reflected to him, as it were, from within, but he stands in a real relationship to things.

He experiences the spiritual of the things; only he translates it into the form of universalia post rem.

1922-09-GA215

Philosophy, Cosmology & Religion

1922-09-06-GA215

Philosophy the course of all knowledge — the past, thanks to awareness of the etheric body — substantial and abstract thought.

1922-09-07-GA215

Philosophy in the past made possible by a condition of half-awake consciousness during which men perceived images. Developed thought can lead to separation from the physical body. Imaginative consciousness gives to philosophy its substance.

1922-09-09-GA215

Knowledge of the planetary cosmos through inspiration in the eternal human entity. As the corpse is produced by the etheric, so thoughts are corpses produced by our living forces. Philosophy can reach this conception through deduction.

1922-09-11-GA215

The soul dives down into the etheric of the cosmos to construct its own etheric body — it keeps an unconscious memory of its extra-earthly activity; imaginative thinking can find it again and thus build a true philosophy.

WORK AREA

1905-01-09-GA262

-p. 86 (a letter to Marie von Sivers)

Note: This quote could be edited down to just the last sentence.

In den Köpfen der sogenannten Theosophen wird sich noch einmal aller Materialismus unseres Zeitalters am krassesten spiegeln. Weil die theosophische Gesinnung selbst eine so hohe ist, werden diejenigen, die nicht ganz von ihr ergriffen werden, gerade die schlimmsten Materialisten werden. An den Theosophen werden wir wohl noch viel böseres zu erleben haben, als an denen, die nicht von der theosophischen Lehre berührt worden sind. Die theosophische Lehre als Dogmatik, nicht als Leben aufgenommen, kann gerade in materialistische Abgründe führen. ... Ich kann Dir nur sagen, wenn der Meister mich nicht zu überzeugen gewusst hätte, dass trotz alledem die Theosophie unserem Zeitalter notwendig ist: ich hätte auch nach 1901 nur philosophische Bücher geschrieben und literarisch und philosophisch gesprochen.

1905-02-09-GA053

Note: This quote sort of complements the previous one.

I tried to show the gradual education of the human being, the purification of the human being from the psychic to the spiritual, in a book that I wrote some years ago, in my Philosophy of Freedom. You find there in the concepts of the Western philosophy what I have shown now. There you find the development of the soul from kama to manas. I have called ahamkara the ego, manas the “higher thinking”, the pure thinking, and buddhi not yet pointing to the origin the “moral imagination.” These are only other expressions of the one and the same matter.

1922 - conversation W.J. Stein with Rudolf Steiner

(quoted from www.millenniumculmination.net/Aristotelians_and_Platonists.pdf)

I [W.J. Stein] asked Rudolf Steiner how he saw the place of his own philosophical view within the history of philosophy.

He answered:

"I have united two elements.

From Johann Gottlieb Fichte I learned the deed of “I”-activity, which is withdrawn from the outer world.

But from Aristotle I took the fullness of an all-encompassing empiricism.

Only one who knows how to complement Fichte with Aristotle will find the whole of reality; and that was my way."

1923-06-28-GA350

Note: This quote could be grouped together with the GA004 quotes below, but it's of a more general significance (emphasis on independent thinking rather than the book).

Anybody today who has learned something does not think for himself: the Latin language thinks in him, even if he has not learned Latin.

[ . . . ]

People are quite right when they say: the brain thinks. Why does the brain think? Because Latin syntax goes into the brain and the brain thinks quite automatically in modern humanity. What we see running round the world are automatons of the Latin language who do not think for themselves.

[ . . . ]

One cannot think independently with the physical body. One can think with the physical hotly only when—as with Latin—the brain is used like an automaton. But as long as one only thinks with the brain, one cannot think anything spiritual.

[ . . . ]

No one can possibly understand [The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity] who does not think independently. From the beginning, page by page, a reader must become accustomed to using his etheric body if he would think the thoughts in this book at all. Hence this book is a means of education—a very important means—and must be taken up as such.

1 - Theory of Knowledge

1891-GA003 Ch. 4

Until we have understood the act of knowledge, we cannot judge the significance of statements about the content of the world arrived at through the act of cognition.

1928 - Karl Ballmer

quote taken from Andreas Delor Wo bleiben die Platoniker?

Note: The quote by Ballmer is very important, the rest could be edited out. The additional info seems interesting, hence quoting a secondary source.

„Der Kern aller Lehren Rudolf Steiners kann in lapidarerer Weise nicht ausgesprochen werden, als es in dem folgenden Satze geschieht: Im Denken steht der Mensch im Elemente des Ursprungs der Welt, hinter dem etwas anderes zu suchen als sich – den Denker – selbst, für den Menschen keine Veranlassung besteht.“

(Karl Ballmer: „Das Ereignis Rudolf Steiner“, Siegen 1995; der Text stammt jedoch von 1928)

Dieser Satz kam, wie Ballmers Freund und Schüler, der Bildhauer Hans Gessner berichtete, so zustande, dass Rudolf Steiner dem jungen Karl Ballmer die Aufgabe stellte, einen Aufsatz über das Denken zu schreiben – entsprechende Aufgaben pflegte Steiner, wenn er (ausgesprochenoder unausgesprochenerweise) darum gebeten wurde, vielen seiner Schüler zu stellen. Der fertige Aufsatz wurde dann vom „Doktor“ korrigiert, der dazu etwa sagte: „diese Aussage ist interessant, bauen Sie das weiter aus“, „jene Aussage müsste wohl erst noch bewiesen werden“ usw. Kurz und gut, Ballmer musste den Aufsatz noch einmal schreiben – er wurde länger. Nach der zweiten Korrektur noch länger. Auch nach der dritten Korrektur und so eine geraume Zeitlang. Dann kam der Punkt, da der Aufsatz wieder kürzer wurde, konzentrierter. Und noch kürzer. Und als er nach einem insgesamt sehr langen Prozess endlich zu obigem Satz geronnen war, trat der Choleriker Ballmer „zornbebend“ vor Rudolf Steiner hin und sagte: „So Herr Doktor, jetzt ändere ich ihn aber nicht mehr!“ Und der „Doktor“ lächelte und meinte: „Ja, SO würde ich es auch sagen“.

1911-04-08-GA035

the Bologna lecture

If one assumes a priori that the I, together with the content of laws of the world reduced to the form of ideas and concepts, is outside the transcendental, it will be simply self-evident that this I cannot leap beyond itself—that is, that it must always remain outside the transcendental.

But this presupposition cannot be sustained in the face of an unbiased observation of the facts of consciousness. ... Therefore, one will arrive at a better conception of the Ifrom the viewpoint of the theory of knowledge, not by conceiving the I as inside the bodily organization and receiving impressions “from without,” but by conceiving the I as being itself within the law-conformity of things, and viewing the bodily organization as only a sort of mirror which reflects back to the I through the organic bodily activity the living and moving of the I outside the body in the transcendental. ...

One could then no longer say that the I would have to leap beyond itself if it desired to enter the transcendental; but one would have to see that the ordinary empirical content of consciousness is related to that which is truly experienced in the inner life of Man's core of being, as the mirrored image is related to the real being of the person who is viewing himself in the mirror.

GA004 PoF - Ch. 15

... thinking is neither subjective nor objective, but rather a principle encompassing both sides of reality. When we observe and think, we carry out a process which itself belongs in the course of real happening. Through thinking, within the very realm of experience itself, we overcome the one-sidedness of mere perceiving.

1925-GA028 - Ch. 17

Note: The English translation of this paragraph on rsarchive is defective. The last sentence is missing entirely, and translating wesenhaft as real rather than essential is... entirely arbitrary.

Ich suchte in meinem Buche [GA4] darzulegen, daß nicht hinter der Sinneswelt ein Unbekanntes liegt, sondern in ihr die geistige Welt. Und von der menschlichen Ideenwelt suchte ich zu zeigen, daß sie in dieser geistigen Welt ihren Bestand hat. Es ist also dem menschlichen Bewußtsein das Wesenhafte der Sinneswelt nur so lange verborgen, als die Seele nur durch die Sinne wahrnimmt. Wenn zu den Sinneswahrnehmungen die Ideen hinzuerlebt werden, dann wird die Sinneswelt in ihrer objektiven Wesenhaftigkeit von dem Bewußtsein erlebt. Erkennen ist nicht ein Abbilden eines Wesenhaften, sondern ein Sich-hinein-Leben der Seele in dieses Wesenhafte. Innerhalb des Bewußtseins vollzieht sich das Fortschreiten von der noch unwesenhaften Sinnenwelt zu dem Wesenhaften derselben. So ist die Sinnenwelt nur so lange Erscheinung (Phänomen), als das Bewußtsein mit ihr noch nicht fertig geworden ist.

1925-GA028 - Ch. 17

Note: Same chapter as above.

Denn worin war dieser in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» begründet? Ich sah im Mittelpunkt des menschlichen Seelenlebens ein vollkommenes Zusammensein der Seele mit der Geistwelt. Ich versuchte die Sache so darzustellen, daß sich eine vermeintliche Schwierigkeit, die Viele stört, in Nichts auflöst. Man meint nämlich, um zu erkennen, müsse die Seele - oder das «Ich» - sich von dem Erkannten unterscheiden, dürfe also nicht mit ihm in eins zusammenfließen. Doch ist diese Unterscheidung ja auch dann möglich, wenn die Seele gewissermaßen pendelartig sich zwischen dem Eins-Sein mit dem geistig Wesenhaften und der Besinnung auf sich selbst hin- und herbewegt. Sie wird dann «unbewußt» im Untertauchen in den objektiven Geist, bringt aber das vollkommen Wesenhafte bei der Selbstbesinnung in das Bewußtsein herein.

1922-04-12-GA324A Q&A

(answers to questions; for some reason, rsarchive has replaced the translation with another that's missing this section, but the quote is still cached by Google)

As an observer, you stand outside what you are observing; you must make a radical distinction between subject and object. As soon as you rise to higher levels of knowledge, subjectivity and objectivity cease.

1897-GA006 - Ch 1.

Note: Goethe describes his first meeting with Schiller in A Fortunate Encounter. Here we found that quoting Steiner's retelling was better.

Goethe narrates a conversation that once ensued between Schiller and himself after they had both attended a meeting of the Society for Nature Research in Jena. ...

[Goethe] drew “with many characteristic strokes, a symbolic plant” before Schiller's eyes. ... Goethe had evolved in himself the conception of a plastic, ideal form that was revealed to his spirit when he surveyed the diversity of the plant forms and observed the element common to them all.

Schiller contemplated this form that was said to live, not in the single plant but in all plants, and said, dubiously: “That is not an experience, that is an idea.”

To Goethe these words seemed to proceed from an alien world. He was conscious of the fact that he had arrived at his symbolic form by the same mode of naive perception by which he arrived at the conception of anything visible to the eye and tangible to the hand. To him the symbolic or archetypal plant was an objective being just as the single plant. He believed that this archetypal plant was the result, not of arbitrary speculation, but of unbiased observation.

He could only rejoin: “It may be very pleasing to me if without knowing it, I have ideas and can actually perceive them with my eyes.” ...

Two opposing world-conceptions were confronting each other in this conversation.

- Goethe sees in the idea of an object an element that is immediately present, working and creating within it. ...

- Schiller thinks otherwise. To him the world of ideas and the world of experience are two separate regions. ... Schiller distinguishes two sources of knowledge, because Man's knowledge flows to him from two directions—from without through observation, and from within through thought.

For Goethe there is one source of knowledge only, the world of experience, and this includes the world of ideas.

1819 - von Purkinje: 'Das Sehen in subjektiver Hinsicht'

Werke, Weimarer Ausgabe, II. Abt., Bd. 11, S. 282.

Note: Goethe's description of his experience of the archetypal plant, which complements the previous quote.

Ich hatte die Gabe, wenn ich die Augen schloß und mit niedergesenktem Haupte mir in der Mitte des Sehorgans eine Blume dachte, so verharrte sie nicht einen Augenblick in ihrer ersten Gestalt, sondern sie legte sich auseinander, und aus ihrem Innern entfalteten sich wieder neue Blumen aus farbigen, auch wohl grünen Blättern; es waren keine natürlichen Blumen, sondern phantastische, jedoch regelmäßig wie die Rosetten der Bildhauer. Es war unmöglich, die hervorquellende Schöpfung zu fixieren, hingegen dauerte sie so lange, als mir beliebte, ermattete nicht und verstärkte sich nicht.

Note: In connection with Goethe's terms for the archetypal plant and animal, I found Steiner calling Christ "the archetypal I".

GA002

Der Typus ist der wahre Urorganismus; je nachdem er sich ideell spezialisiert: Urpflanze oder Urtier.

GA139

Es ist eben in jenem großen Wendepunkt der Menschheitsevolution aus dem Hellsehen herangebracht worden an die Ich-Seele des Menschen das Verständnis für die Christus-Wesenheit, das heißt für das Ur-Ich des Menschen.

2 - Philosophy of Spiritual Activity (Philosophy of Freedom)

1894-11-04-GA039

pp. 232-233 (a letter to Rosa Mayreder)

Ich lehre nicht; ich erzähle, was ich innerlich durchlebt habe. Ich erzähle es so, wie ich es gelebt habe. Es ist alles in meinem Buche persönlich gemeint. Auch die Form der Gedanken. Eine lehrhafte Natur könnte die Sache erweitern. Ich vielleicht auch zu seiner Zeit. Zunächst wollte ich die Biographie einer sich zur Freiheit emporringenden Seele zeigen. Man kann da nichts tun für jene, welche mit einem über Klippen und Abgründe wollen. Man muß selbst sehen, darüberzukommen. Stehenzubleiben und erst anderen klarmachen: wie sie am leichtesten darüberkommen, dazu brennt im Innern zu sehr die Sehnsucht nach dem Ziele. Ich glaube auch, ich wäre gestürzt: hätte ich versucht, die geeigneten Wege sogleich für andere zu suchen. Ich bin meinen gegangen, so gut ich konnte; hinterher habe ich diesen Weg beschrieben. Wie andere gehen sollen, dafür könnte ich vielleicht hinterher hundert Weisen finden. Zunächst wollte ich von diesen keine zu Papier bringen. Willkürlich, ganz individuell ist bei mir manche Klippe übersprungen, durch Dickicht habe ich mich in meiner nur mir eigenen Weise durchgearbeitet. Wenn man ans Ziel kommt, weiß man erst, daß man da ist. Vielleicht ist aber überhaupt die Zeit des Lehrens in Dingen, wie das meine, vorüber. Mich interessiert die Philosophie fast nur noch als Erlebnis des Einzelnen.

Note: Steiner repeats the last statement of this quote in a different way at the bottom of the next page, making a comparison with Euclid's axioms.

I [W.J. Stein] then asked Rudolf Steiner:

“After thousands of years have passed, what will still remain of your work?”

He answered,

“Nothing except The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. But everything else is contained within it. When someone actualizes the deed of freedom depicted there, he will find the whole content of Anthroposophy.”

1922 - Rudolf Steiner in conversation with W.J. Stein

quoted from: www.millenniumculmination.net/Aristotelians_and_Platonists.pdf

Three elements are interwoven in every experience of freedom. To immediate experience, they appear as a unity; but with the passage of time, they can enter into consciousness as separate entities. One experiences what one is going to do as an inner picture that arises through the free activity of Moral-Imagination. Because one loves it, what one decides to do appears as a true Imagination [cf. Goethe's "Duty: where a man loves what he commands himself to do."].

The second element that is woven into this unified experience, is that higher powers admonish us to follow the impulse that is arising within us. ‘Do it,’ the inner voices say, and becoming aware of this is a perceptible Inspiration.

Yet there is still a third element woven into this unified experience: Through this free deed one places oneself within outer arenas of destiny into which one would otherwise never have entered. One encounters other people, is led to other places; what was first grasped inwardly through Intuition now approaches one externally as new destiny. This occurs when true Intuition unfolds…

You see, these three experiences that are interwoven into one are later separated out, come to consciousness in isolation, so that Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition become conscious as acts of cognition.

1922-04-10-GA082

pp. 116, 143

Note: GA82 seems to coincide with the conversation quoted above (same year, same city). It has multiple long passages about GA4 and related subjects.

Sie können im Grunde genommen schon alles, was erstes, sagen wir, Axiom, was erstes Elementarstes ist, um die anthroposophische Forschungsmethode zu durchschauen, in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit», ja, in noch älteren meiner Bücher finden.

[ . . . ]

Das ist ebenso, wie wenn man die Axiome des Euklid liest auf der ersten Seite eines Geometriebuches und einen Begriff bekommt, was da kommen wird. Wie dann die ganze Geometrie folgt aus diesen Axiomen, so ist, wie axiomatisch, in der wirklichen Einsicht in die sittliche Welt vorhanden ihrer Wesenheit nach die ganze geistige Welt. Aber es darf deshalb niemand glauben, daß er die Natur der geistigen Welt kennt, wenn er nur die Natur der moralischen Impulse kennt. Er kennt nur das Axiomatische, das Elementare.

1922-05-07-GA212

My Philosophy of Freedom has been called the most extreme philosophy of individualism. It cannot be anything else because it is the most Christian of philosophies. Thus, one must place on one side of the scales everything that can be attained through knowledge of the laws of nature, which can only be penetrated with spirituality by ascending to pure independent thinking. Independent thinking can still be restored within pure technical knowledge. However, there must be placed on the other side of the scales a true recognition of Christ, a real understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha.

[ . . . ]

In my Philosophy of Freedom, when I spoke of knowledge of external nature, I presupposed only the kind of concepts needed for understanding a steam engine. However, in order to understand a steam engine, one must set aside one's whole human personality except for the very last: pure thinking.

1917-09-04-GA176

Note: This quote can go into many different subsections. Put here because the previous quoted lecture mentions Paul too (although not the previous quote itself).

Kant said that the world is our mental picture, for the mental pictures we make of the world are formed according to the way we are organized.

I may mention, not for personal but for factual reasons, that this Kantianism is completely refuted in my books Truth and Knowledge and The Philosophy of Freedom. These works set out to show that when we form concepts about the world, and elaborate them mentally, we are not alienating ourselves from reality. We are born into a physical body to enable us to see objects through our eyes and hear them through our ears and so on.

What is disclosed to us through our senses is not full reality, it is only half reality. ... The task of real knowledge and therefore real science is to turn half reality; i.e., semblance, into the complete reality. The world, as it first appears through our senses, is for us incomplete. This incompleteness is not due to the world but to us, and we, through our mental activity, restore it to full reality.

These thoughts I venture to call Pauline thoughts in the realm of epistemology. For it is truly nothing else than carrying into the realm of philosophic epistemology, the Pauline epistemology that Man, when he came into the world through the first Adam, beheld an inferior aspect of the world; its true form he would experience only in what he will become through Christ.

The introduction of theological formulae into epistemology is not the point; what matters is the kind of thinking employed. I venture to say that, though my Truth and Knowledge and The Philosophy of Freedom are philosophic works, the Pauline spirit lives in them. A bridge can be built from this philosophy to the Christ Spirit; just as a bridge can be built from natural science to the Father Spirit. By means of natural-scientific thinking the Christ Spirit cannot be attained. Consequently as long as Kantianism prevails in philosophy, representing as it does a viewpoint that belongs to pre-Christian times, philosophy will continue to cloud the issue of Christianity.

GA028 - Ch. 23

The problem can by no means be – so I said to myself again and again – to answer this question: Is Man's will free or not? – but to answer this quite different one:

How is the way to be attained in the life of the mind which leads from the unfree natural will to that which is free – that is, which is truly moral?

... Freedom has its life in human thought; and it is not the will which is of itself free, but the thinking which empowers the will.

So, therefore, in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity I had found it necessary to lay all possible emphasis upon the freedom of thought in discussing the moral nature of the will.

1923-01-06-GA326

[In my Philosophy of Freedom] I demonstrated how this semblance, inherent in pure thinking, becomes the impulse of freedom when inwardly grasped by man in thinking. If something other than semblance were contained in our subjective experience, we could never be free. But if this semblance can be raised to pure thinking, one can be free, because what is not real being cannot determine us, whereas real being would do so.

1921-11-29-GA079

In the early nineties of the past century I wrote my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. The task of this book was to establish the experience, the fact of freedom. From Man's own inner experiences I sought to characterise the consciousness of freedom as an absolute certainty. ...

Those who study my book Philosophy of Spiritual Activity will find however I was obliged to renounce speaking of freedom of the human will at first, and to speak instead of a freedom experienced in thought, in pure thinking emancipated from the senses. In thoughts which consciously arise in the human soul as an ethical, moral ideal, in thoughts which have the strength to influence the human will and to lead it to action, in such thoughts there is freedom. We can speak of human freedom when we speak of human actions shaped by Man's own free thinking, when he reaches the point, through a moral self-training, of not allowing his actions to be influenced by instincts, passions, emotions or by his temperament, but only by the devoted love for an action. In this devoted love for an action, can develop something which proceeds from the ideal strength of pure ethical thinking. This is a really free action.

Individualism

Note: This and the following quotes are important and warrant a separate header.

1899-GA030 - Individualism in Philosophy

To comprehend the “I” in thinking means to create the basis for founding everything that comes from the “I” also upon the “I” alone.

The “I” that understands itself can make itself dependent upon nothing other than itself. And it can be answerable to no one but itself. After these expositions it seems almost superfluous to say that with this “I”, only the incarnate real “I” of the individual person is meant and not any general “I” abstracted from it. For any such general “I” can indeed be gained from the real “I” only by abstraction. It is thus dependent upon the real individual.

1900-GA30 - The Genius

Man should not become selfless; he cannot. And anyone who says he can is lying. But selfishness can rise to the highest world interests. I can concern myself with the affairs of all mankind because they interest me as much as my own, because they have become my own. Stirner's "owner" is not the narrow-minded individual who encapsulates himself and lets the world be the world; no, this "owner" is the true representative of the world spirit who acquires the whole world as his "property" in order to treat the affairs of the whole world as his own. Only expand your self to the world-self first, and then act egoistically all the time. Be like the farm wife who sells eggs at the market. Only don't do the egg business out of selfishness, but do the world business out of selfishness! ... Do not preach to men that they should be unselfish, but plant in them the highest interests, so that their selfishness, their egoism, may attach itself to them. Then you will ennoble a power that really lies in Man; otherwise you will be talking about something that can never exist, but which can only turn people into liars.

4 - Pure Thinking

● Note: I believe this quote can be connected with the one on the Enlivened images page, about matter-free thought.

Another relevant thing, if this isn't already on a schema, GA26 Leading Thoughts talks about the gradual descent of thought from the 'I' to the physical body (compare the last sentence of this quote). -> no that is not on a schema yet, can you be more specific?

1922-04-12-GA082

p. 217-218

Der Gnostiker fühlte die Realität des Denkens, indem er anschaute. Unser Denken hat ein bloßes Bilddasein. Was folgt daraus, wenn wir wirklich zu diesem reinen Denken aufsteigen und in ihm unsere moralischen Impulse fassen? Nun, wenn ich hier einen Spiegel habe, darinnen Bilder, so können die Spiegelbilder mich nicht durch Kausalität zu irgend etwas zwingen. Will ich mich durch Spiegelbilder zu irgend etwas veranlassen lassen, ist mein Denken in der Weltenentwickelung der Menschheit so weit fortgeschritten, daß es wirklich nur Bildcharakter hat, dann enthält es für mich nicht mehr Kausalität. Dann wird das reine Denken, wenn ich moralische Impulse habe, gebildet zu Impulsen der menschlichen Freiheit. Dadurch, daß wir zum Phänomenalismus gekommen sind, damit aber zum reinen Bilddenken, und dadurch, daß wir aus der Kraft des reinen Bilddenkens moralische Impulse fassen können, gehen wir auch durch das Stadium der Freiheit. Wir erziehen uns die Freiheit in unser Menschenwesen ein, indem wir diese Phase menschlicher Entwickelung durchmachen. Das wollte ich darstellen in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit». Wir werden aber nur frei, wenn wir ein Denken haben, das Bilddenken ist, das ganz im physischen Leibe verläuft, wie ich es beschrieben habe.

1922-10-12-GA217

Thus the basis for all Anthroposophy is inner activity, the challenge to inner activity, the appeal to what can be active when all the senses are silent and only the activity of thinking is astir. ... What I called pure thinking in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity was certainly not well named when judged by outer cultural conditions.

For Eduard von Hartmann said to me: “There is no such thing, one can only think with the aid of external observation.”

And all I could say in reply was: “It has only to be tried and people will soon learn to be able to make it a reality.” Thus take it as a hypothesis that you could have thoughts in a flow of pure thought. Then there begins for you the moment when you have led thinking to a point where it need not be called thinking any longer, because in a twinkling—in the twinkling of a thought—it has become something different. This rightly named pure thinking has at the same time become pure will, for it is willing, through and through. If you have advanced so far in your life of soul that you have freed thinking from outer perception, it has become at the same time pure will.

5 - Miscellaneous

Note: A quote about Locke's primary and secondary qualities, which is useful even without any knowledge of him. There's a sort of related and well-known thought experiment called Mary's Room, not sure it's even worth mentioning; Steiner formulates it much more adequately and deals with it in his writings on Goethe.

1923-01-01-GA326

If we want to discover the nature of geometry and space, if we want to get to the essence of Locke's primary qualities of corporeal things, we must look within ourselves. ... Man experiences [secondary qualities, such as sound, color, warmth, smell and taste] outside his physical and etheric body, and projects only the images into himself. Because the scientific age no longer saw through this, mathematical forms and numbers became something that man looked for abstractly in the outer world. The secondary qualities became something that man looked for only in himself. But because they are only images in himself, man lost them altogether as realities.

1922-09-13-GA215

Note: Augustine and Descartes.

When we advance through meditation to imaginative perception we cross over an abyss, as it were. Our thinking ceases, a state of non-thinking exists between ordinary thinking and the active, life-filled thinking of imagination.

Several philosophers have experienced this non-thinking—for instance, Augustine and Descartes—but they were unable to interpret it correctly. They spoke of the doubt that arises at the start of philosophical thinking. This doubt that Augustine and Descartes spoke about is only the reflection, brought into ordinary consciousness, of this condition of non-thinking that Man finds himself in between ordinary thinking and imaginative thinking.

Since neither Augustine nor Descartes had submerged their souls into this actual non-thinking, they did not come to the true experience, only the reflection, of what a person experiences when his thinking, particularly the thoughts of memory, ceases between ordinary and imaginative thinking. The doubt of Augustine and Descartes is only the reflected image in ordinary consciousness of this experience that does not appear until the transition into imaginative consciousness. Thus, when we observe it in the light of imaginative philosophy, we can correctly interpret what appears vaguely in the mere philosophy of ideas.

1919-11-23-GA194

Note: This quote is related to the above via Descartes and unreality of our ordinary thinking.

“I think, therefore I am.”

That is the opposite of the truth. When we think we are not; for in thinking we have merely the image of reality.

Thinking would be of no consequence for us if we would exist within reality with our thinking, if thinking were not merely an image. We must become conscious of the mirror-character of our world of mental images, of our world of thoughts. The moment we become conscious of this mirror character we shall appeal to a different source of reality within us. Of this, Michael wills to speak to us. That means, we must try to recognize our thought world in the mirror-character; then we shall work against the Luciferic evolution. For the latter is greatly interested in pouring substance into our thinking, in trying to delude us with the erroneous belief that thinking is permeated by substance. Thinking contains no substance, but merely image. We shall take substance out of other and deeper levels of our consciousness. ... [We] do not send out of the deeper levels of our being into thoughts themselves that which ought to be in them.

1920-05-23-GA074

Note: the lecture cycle on Thomism should have it's own separate subheader. This introductory quote could be trimmed down to a couple of sentences.

The sinfulness of the reason was, in a way, responsible for the thinkers before Albertus and Thomas speaking of two truths. ... They put the question to themselves: How does Christ redeem in us the truth of the reason which contradicts revealed spiritual truth?

[ . . . ]

They were not yet far enough to be able to apply the redemption of man from original sin to human thought. Therefore, Albertus and Thomas had to deny reason the right to mount the steps which would have enabled them to enter into the spiritual world itself. And Scholasticism left behind it the question: How can human thought develop itself upward to a view of the spiritual world? The most important outcome of Scholasticism is even a question, and is not its existing content. It is the question: How does one carry Christology into thought? How is thought made Christ-like?

[Added from the next lecture:]

The advance of mankind in the future must be, not only to find the principle of redemption for the external world, but also for human reason.

Other Authors

Nietzsche

1894-12-23-GA039

p. 238 (a letter to Pauline Specht)

Note: On the connection with Nietzsche and his works. This quote could go together with a reference to Steiner's book about Nietzsche, GA005.

Ist Ihnen Nietzsches «Antichrist» vor Augen gekommen? Eines der bedeutsamsten Bücher, die seit Jahrhunderten geschrieben worden sind! Ich habe meine eigenen Empfindungen in jedem Satze wiedergefunden. Ich kann vorläufig kein Wort für den Grad der Befriedigung finden, die dieses Werk in mir hervorgerufen hat. ... Ich empfinde Nietzsches Erkrankung besonders schmerzlich. Denn ich habe die feste Überzeugung, daß meine «Freiheitsphilosophie» an Nietzsche nicht spurlos vorübergegangen wäre. Er hätte eine Menge von Fragen, die er offengelassen hat, bei mir weitergeführt gefunden und hätte mir gewiß in der Ansicht recht gegeben, daß seine Moralansicht, sein Immoralismus, seine Krönung erst in meiner «Freiheitsphilosophie» findet, daß seine «moralischen Instinkte» gehörig sublimiert und auf ihren Ursprung verfolgt das geben, was bei mir als «moralische Phantasie» figuriert. Dieses Kapitel «Moralische Phantasie» meiner «Freiheitsphilosophie» fehlt geradezu in Nietzsches «Genealogie der Moral», trotzdem alles, was in derselben steht, darauf hinweist. Und der «Antichrist» ist nur eine besondere Bestätigung dieser meiner Ansicht.

Unger

GA082

p. 248

Note: Steiner about Unger.

Die Natur des menschlichen Erkenntnisprozesses in lichtvoller, klarer Analyse zu durchschauen und das Durchschaute in synthetischer Art zu einem wirklichen Bilde des Erkennens zu machen, war sein von denkerischem Scharfsinn getragenes Bestreben. Unger ist nicht Dialektiker, sondern Beobachter der empirischen Erkenntnis-Tatbestände. ... Dabei ist Ungers Denken geschult an den technischen Problemen, ist dadurch frei von jeder subjektiven Verschwommenheit, und deshalb ist seine wissenschaftliche Mithilfe in der Anthroposophie die denkbar bedeutungsvollste.

Bely

1917-01-21-GA173C

I should like to draw your attention to a book—you will excuse my inability to tell you the title in the original language—just published by our friend Bugaev under his pen-name of Andrei Belyi. The book is in Russian and gives a very detailed account in great depth of the relationship between spiritual science and Goethe's view of the world. In particular it goes into the connections between Goethe's views and what I said in Berlin in the lecture cycle Human and Cosmic Thought about various world views, but it also discusses a good deal that is contained in spiritual science. Its connections to Goethe's views are discussed in depth and in detail and it is much appreciated that our friend Bugaev has published a revelation of our spiritual-scientific view in Russian.

GA176

pp. 59-60

Note: This is a long quote; if used at all, it should be edited. Bely is mentioned as "a friend", not by his name.

Reale Dinge zu studieren fällt den Menschen heute gar nicht ein. Wo reale Dinge auftreten, da empfinden die Menschen heute gar nichts mehr Rechtes. Einer unserer Freunde hat versucht, dasjenige zusammenzubinden, was ich in meinen Büchern über Goethe geschrieben habe, mit dem, was ich einmal hier vorgetragen habe über den menschlichen und kosmischen Gedanken. Er hat ein russisches Buch daraus gemacht, ein merkwürdiges russisches Buch. Das Buch ist schon erschienen. Ich bin überzeugt davon, es wird in Rußland von einer gewissen Schichte der Bevölkerung außerordentlich viel gelesen werden. Würde es ins Deutsche übersetzt werden oder in andere europäische Sprachen, so würden es die Leute sterbenslangweilig finden, weil sie keinen Sinn haben für die fein ausziselierten Begriffe, für die wunderbare Filigranarbeit der Begriffe, möchte ich sagen, die da gerade in diesem Buche auffällt. Es ist dieses ganz merkwürdig, daß im russischen Charakter, wie er sich entwickeln wird, etwas ganz anderes auftreten wird als im übrigen Europa, daß da nicht wie im übrigen Europa Mystik und Intellektualität getrennt leben werden, sondern eine mystische Natur sich ausleben wird, die selbst intellektualistisch wirkt, und eine Intellektualität, die nicht ohne mystische Grundlage bleibt, daß da etwas ganz Neues heraufkommt: eine Intellektualität, die zugleich Mystik ist, eine Mystik, die zugleich Intellektualität ist, aber schon so gewachsen, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf. Dafür ist nicht das geringste Verständnis vorhanden, und doch ist das dasjenige, was in diesem östlichen Chaos jetzt aber noch ganz verborgen lebt, denn es wird erst in dieser Eigenart, die ich nur in ein paar Strichen angedeutet habe, sich ausleben. Aber um diese Dinge zu verstehen, muß man eben das Gefühl haben für die Realität der Vorstellungen; für die Wirklichkeit der Ideen. Das ist aber heute so notwendig wie nur irgend etwas, daß man sich diese Empfindung, dieses Gefühl für die Wirklichkeit der Ideen aneignet, sonst wird man immer wieder und wiederum abstrakte politische Programmpunkte, schöne politische Reden halten für etwas, was wirklich schöpferisch sein könnte, während es nicht wirklich schöpferisch sein kann. Man wird keine Empfindung gewinnen können für diejenigen Punkte in der Geschichte, die sehr lehrreich sein könnten, in denen, wenn man sie wirklich verfolgt, ein Etwas auftritt, was auch für die Gegenwart außerordentlich lehrreich sein könnte.

Ballmer & Swassjan as Philosophers of Anthroposophy

Both Ballmer and Swassjan dedicate their work to elaborating Steiner's ideas philosophically, attaching central importance to his theory of knowledge, and in the context of history of philosophy and culture.

Their philosophy is an always being conscious of thinking and the thinking subject — or Max Stirner's individualism continued further using Goethe's method (expanded to encompass philosophy), as it was first continued by Steiner himself.

Karl Ballmer

Karl Ballmer (1891-1958) met Rudolf Steiner in 1918, who asked him to collaborate on the artistic design of the first Goetheanum. He devoted the rest of his life to trying to draw the educated world's attention to 'the Rudolf Steiner event', as he called anthroposophy.

He published extensively, see de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Ballmer#Publikationen

Selected reading

- On Steiner's GA004: 'Deutschtum und Christentum in der Theosophie des Goetheanismus' (1935)

- Ballmer treats Rudolf Steiner's 'Philosophy of Freedom' as "an analysis of Christ-Consciousness" in his Deutschtum und Christentum.

- On Steiner's GA003: 'Die Karma-Orientierung der Erkenntnistheorie' (1941)

- A list of digital editions with links and synopses (in DE)

.

1932-09-02 - Karl Ballmer

(a letter to Marie Steiner)

I owe my existence to Rudolf Steiner (literally). From the age of 20 to 27, I was a highly dangerous suicide candidate out of despair for the meaning of life. ... Boos gave me the transcripts of Rudolf Steiner's lectures to read, and I realized and declared: this is science as art. Now I could begin to find my bearings towards the meaning of life. I soon got to know this meaning for myself personally in Rudolf Steiner.

It is literally true that I owe my present existence to Rudolf Steiner and it is my holy will to dedicate my entire being to the responsibility for Rudolf Steiner's work and influence. This is the meaning of my karma.

Swassjan

Karen A. Swassjan (1948-2024) was an Armenian philosopher, literary critic, historian of culture and anthroposophist. He wrote his doctoral thesis on Henri Bergson and translated and edited works by Rainer Maria Rilke, Friedrich Nietzsche and Oswald Spengler.

Publications, see: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karen_Swassjan

Selected reading

- 'The Ultimate Communion of Mankind: A Celebration of Rudolf Steiner's Book The Philosophy of Freedom' (1997)

- 'Sartre: A Blind Witness of Anthroposophy' (2005) (also in FR, RU, and in DE in Der Europäer Jun 2005)

- 'Die Karl Ballmer Probe' (1994)

- 'Permanenz der Auferstehung' (2007)

.

Swassjan - An Outline of Philosophy in Self-presentation

We say farewell to the Greek founding fathers of philosophy and learn that the essence of a thing is not idea, entelechy, telos, or, if you will, "whatness" but — with all shocking clarity — THE INNER WORLD OF THE MAN THINKING THE THING.

A thing, a cognized, comprehended, understood thing, is the Man himself: not in a figurative, but in the literal sense. In the soul, consciousness, self-consciousness of a Man, the world isn't just happening, but also knows about itself that it is the world and that it is happening.

It took thousands of years for consciousness to become conscious of itself as that which it is.

1923-05 - Tsvetaeva

Note: This quote is not directly related to philosophy. It's a diary entry by Tsvetaeva after attending a lecture by Steiner. She knew Bely, but she didn't know much about anthroposophy. The entire diary entry is slightly longer, and at the start she writes that she didn't really listen to the lecture, but was fascinated by Steiner's way of speaking (comparing him with a saint and a martyr).

A queue of clerks in front of the clairvoyant: I'm at the very end. The last one. (To everyone else — more urgent!) Standing, agonizing: he's so tired — and then there's also I... But: I, that's not just all these here. And — if he's clairvoyant... While agonizing — already standing before him. That youth — a thousand years old. The face a web of finest wrinkles. The finest work of time. A step back — and a youth again. But I'm standing — and as if by Leonardo's hand, old age. Not old age — ancient brittleness. Not ancient brittleness — ghostliness. Any moment, and he'll crumble into dust. (How long have I been standing? A second?)

And, taking heart and a breath, "Herr Doktor, sagen Sie mir ein einziges Wort — fürs ganze Leben!" [Doctor, tell me a single word — for the entire life!]

A long pause and, with a heavenly smile, mit Nachdruck, "Auf Widersehn!" [with emphasis, "See you again!"]

Discussion

Note 1 - Mathematics and philosophy

Introduction

About the 'unsolved' philosophical problem of mathematical reality, and whether mathematics is a product of the mind or have a separate reality by itself?

See also: Book of Ten Pages

Background: Mathematical reality debate

The connection between mathematics and material reality has led to philosophical debates since at least the time of Pythagoras, over 2500 years ago. The debate may be roughly partitioned into two opposing schools of thought:

- platonism, which asserts that mathematical objects are real, and

- formalism, which asserts that mathematical objects are merely human constructions.

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato argued that mathematical abstractions that reflect material reality have themselves a reality that must exist outside space and time, that while mathematical entities are abstract, they have, in fact, no spatiotemporal or causal properties, and are eternal and unchanging. This is often claimed to be the view most people, if asked, currently have of numbers.

The term Platonism is used in this position since such a view is seen to parallel Plato's Theory of Forms and a ”World of Ideas” (Greek: eidos (εἶδος)). Plato's Theory of Forms are described in the Allegory of the cave: the everyday world can only imperfectly approximate an unchanging, ultimate reality. Both Plato's cave and Platonism have meaningful, not just superficial connections, mostly on account Plato's ideas were preceded and probably influenced by the highly popular Pythagoreans of ancient Greece and Rome, who believed that the world was, quite literally, generated by numbers.

Major unsolved questions considered in mathematical Platonism are:

• Precisely where and how do mathematical entities exist, and how do we know about them?

• Is there a world, completely separate from our physical one, that is occupied by the mathematical entities?

• If this separate world does exist, how can we gain access to it and discover truths about these entities and whatever else may be there?

Today, it is generally found most modern mathematicians act as though they are Platonists, since they think of and talk of their entities of study as real objects, however, if pressed to defend the position carefully, many will retreat to formalism.

To complicate maters further, Bertrand Russell argued that formalism still fails to explain what is meant by the linguistic application of numbers in statements such as ”there are three men in the room”.

References

Bertrand Russell

and the “unsolved“ philosophical problem of mathematical reality. Is mathematics a product of the mind or does it have a separate reality by itself?

from 'Portraits From Memory And Other Essays' (1950); Essay: V. Beliefs: Discarded and Retained,

Take, for instance, numbers: when you count, you count “things,” but “things” have been invented by human beings for their own convenience. This is not obvious on the earth's surface because, owing to the low temperature, there is a certain degree of apparent stability. But it would be obvious if one could live on the sun where there is nothing but perpetually changing whirlwinds of gas. If you lived on the sun, you would never have formed the idea of “things,” and you would never have thought of counting because there would be nothing to count. In such an environment, even Hegel's philosophy would seem to be common sense, and what we consider common sense would appear as fantastic metaphysical speculation.

Such reflections have led me to think of mathematical exactness as a type of human dream, and not as an attribute of an approximately knowable reality. I used to think that of course there is exact truth about anything, though it may be difficult and perhaps impossible to ascertain it. Suppose, for example, that you have a rod which you know to be about a yard long. In the happy days when I retained my mathematical faith, I should have said that your rod certainly is longer than a yard or shorter than a yard or exactly a yard long. Now I should admit that some rods can be known to be longer than a yard and some can be known to be shorter than a yard, but none can be known to be exactly a yard, and, indeed, the phrase “exactly a yard” has no definite meaning.

Exactness, in fact, was a Hellenic myth which Plato located with God in heaven. He was right in thinking that it can find no home on earth. To my mathematical soul, which is attuned by nature to the visions of Pythagoras and Plato, this is a great sorrow. I try to console myself with the knowledge that mathematics is still the necessary implement for the manipulation of nature. If you want to make a battleship or an atom bomb, if you want to develop a kind of wheat which will ripen farther north than any previous variety, it is to mathematics that you must turn. Mathematics, which had seemed like a surgeon's knife, is really more like the battle-ax. But it is only in applications to the real world that mathematics has the crudity of the battle-ax. Within its own sphere, it retains the neat exactness of the surgeon's knife.

The world of mathematics and logic remains, in its own domain delightful; but it is the domain of imagination. Mathematics must live, with music and poetry, in the region of man-made beauty, not amid the dust and grime of the world below.

1922-04-08-GA082

read in full, Rudolf Steiner covers the question of the true nature of mathematics

The fundamental attitude of consciousness in anthroposophy has been drawn from that branch of present-day science which is least of all attacked in respect to its scientific character and importance. I admit, however, that many of our adherents—and opponents too—fail to perceive correctly what I have now to characterise by way of introduction.

The position of mathematics among the sciences has already been mentioned. Kant's pronouncement, that in every science there is only as much real knowledge—real cognition—as there is mathematics, is widely known.

Now I have not to deal here with mathematics itself, with its value for the other sciences and in human life, but rather with the mental attitude a Man assumes when “mathematicising”—if I may use this word; that is, when actively engaged in mathematical thinking. His attitude of soul is then, indeed, quite distinctive. Perhaps we may best characterise it by speaking, first, of that branch of mathematics which is usually called geometry and, at least in those parts of it known to the majority of people, has to do with space, is the science of space.

...

What I am here describing is the ascent to so-called “imaginative perception” (imaginative Anschauung). Every human being today has the same space-world—unless he be abnormally mathematical or unmathematical. What can live in us in like manner, and in such a way that we experience with it the world as well, can be acquired by exercises. “Imaginative perception”—a technical term that does not denote “fancy” or “imagination” in the usual sense—can be added to the ordinary objective perception of objects (in which mathematics is our sure guide), and will open up a new region of the world.

I said yesterday that I would have to expound to you a special method of training and research. I must describe what one has to do in order to attain to such “imaginative perception”. In this we come to perceive as a whole the qualitative element in the world—just as, in a sense, we come to perceive space (which has, at first, no reality that engages our higher interests) as a whole. When we are able to confront the world in this way, we are already at the first stage of super-sensible perception. Sense-perception may be compared to that perception of things in which we do not distinguish between triangular and rectangular shapes, do not see geometrical structures in things, but simply stare at them and only take in their forms externally. But the perception that is developed in “Imagination” is as much involved with the inner essence of things as mathematical perception is with mathematical relationships.

If we approach mathematics in the right frame of mind, we come to see precisely in the mathematician's attitude when “mathematicising” the pattern for all that one requires for super-sensible perception. For mathematics is simply the first stage of super-sensible perception.

The mathematical structures we “perceive” in space are super-sensible perceptions—though we, accustomed to “perceive” them, do not admit this. But one who knows the intrinsic nature of “mathematicising” knows that although the structure of space has no special interest at first for our eternal human nature, mathematical thinking has all the characteristics that one can ask of clairvoyance in the anthroposophical sense: freedom from nebulous mysticism and confused occultism, and the sole aim of attaining to the super-sensible worlds in an exact, scientific way.

Note 2: On Kant vs Hegel

1961-05-15 - Ayn Rand

transcript from extract of interview by James McConnell, see youtube here for full interview, and short on youtube

interviewer:

well you mentioned cat you mentioned aristotle and his influence on the renaissance um who under whose influence was the world before the renaissance let's go back and look at some of them sounds the middle ages dark ages were ruled by mysticism that is by religion and philosophy and in those periods the philosophy was considered a handmaiden of theology the predominant philosophical influence was plato plato through platinus and augustine who were philosophically platinus aristotle's triumph in effect began with thomas aquinas who who brought back the philosopher's status most particularly its most important part epistemology logic reason

well what in particular about Kant's system of philosophy .. do you think was responsible for the trend that we see today in philosophy?

Ayn Rand

the very cumbersome, very complex, and very false and phony system of dividing men's intellect, men's mind from reality ..

is declaring that what we perceive is only an illusion created by some special kind of categories in forms of perception in our own mind

by declaring and allegedly proving - allegedly - that we can never perceive things as they are ...

which simply means that: any object which is perceived, is thereby false

if an object is perceived .. it means our perception is incorrect

it was in effect an attack on the whole concept of consciousness .. not only human consciousness but any consciousness

it was the denial of the reality or the validity of our perceptions

Related pages

- Worldview Spiritual Science

- Freedom

- Meaning of life (also teleology and cosmogony)

- Man's most important questions

- Meaning of Free Man Creator

- D00.003 - Systemic aspects of the study process

Philosophy of Freedom resources

- Freedom#Philosophy of Freedom resources:

- Navigating anthroposophical resources#Note 1 - Study companions for GA volumes

Epistemology

- Goethe#Goethean science

- Relationship between mineral and spiritual science#Note 2 - Bridging the gap - New developments in scientific research: Part 1

References and further reading

- Carl Unger: 'Die Autonomie des philosophischen Bewußtseins' (1921)

- Franz Brentano: 'Die vier Phasen der Philosophie und ihr augenblicklicher Stand : nebst Abhandlungen über Plotinus, Thomas von Aquino, Kant, Schopenhauer und Auguste Comte' (1926, 1968)

- Andrew Welburn: 'Rudolf Steiner's Philosophy' (2012)

- Jost Schieren (editor/publisher): 'Die philosophischen Quellen der Anthroposophie' (2022)

internet

overview classic reference works of philosophy

- Aristotle (384–322 BC)

- Nicomachean Ethics

- Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

- Critique of Practical Reason, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

- Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814)

- The Science of Knowledge (Wissenschaftslehre), Foundations of Natural Right

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831)

- Phenomenology of Spirit, Elements of the Philosophy of Right

- Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900)

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil (1886) and On the Genealogy of Morality (1887)

- Rudolf Steiner

- Richard Seddon: 'Philosophy as an approach to the spirit : An introduction to the fundamental works of Rudolf Steiner' (2005)