Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci

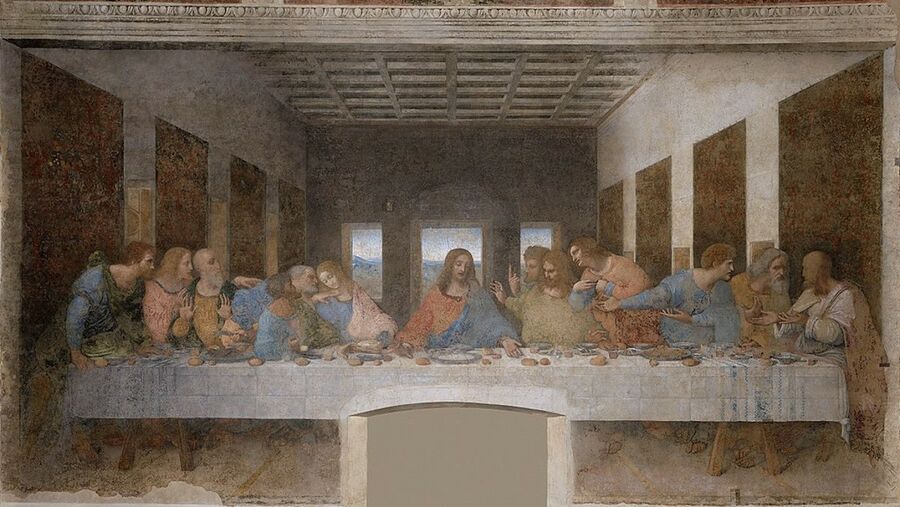

The Last Supper or Holy Supper is one of the most famous paintings on Earth, and contains intriguing symbolism that has been the subject of a wide range of literature and speculation. It was painted by Leonardo da Vinci most probably in the period 1495–1498.

The painting depicts the moment that Jesus predicts his betrayal during the during the Last Supper, see also Matthew 26:24–25, Mark 14:18–21, Luke 22:21–23, and John 13:21–30.

The meaning of the painting comes to live in the symbolism of the twelve apostles and how it relates to old rites of initiation (see Holy Supper symbolism - bread and wine). The twelve apostles represent future stages of human development, and can be linked to future cultural ages.

Aspects

- the painting also represents the duality between the cosmic divine and the earthly, and in its form maybe also the duality between euclidean and projective geometry as representing the central (gravitational) and peripheral (etheric formative) forces.

- references to the number three: the apostles are seated in groups of three, there are three windows behind Jesus (and the shape of Jesus' figure resembles a triangle)

- other 'hinein-interpretiering' studies have found the painting to include the golden ratio (in the ratios of the composition) and even the Fibonacci series. See also examples Schema FMC00.021D and Schema FMC00.021F below.

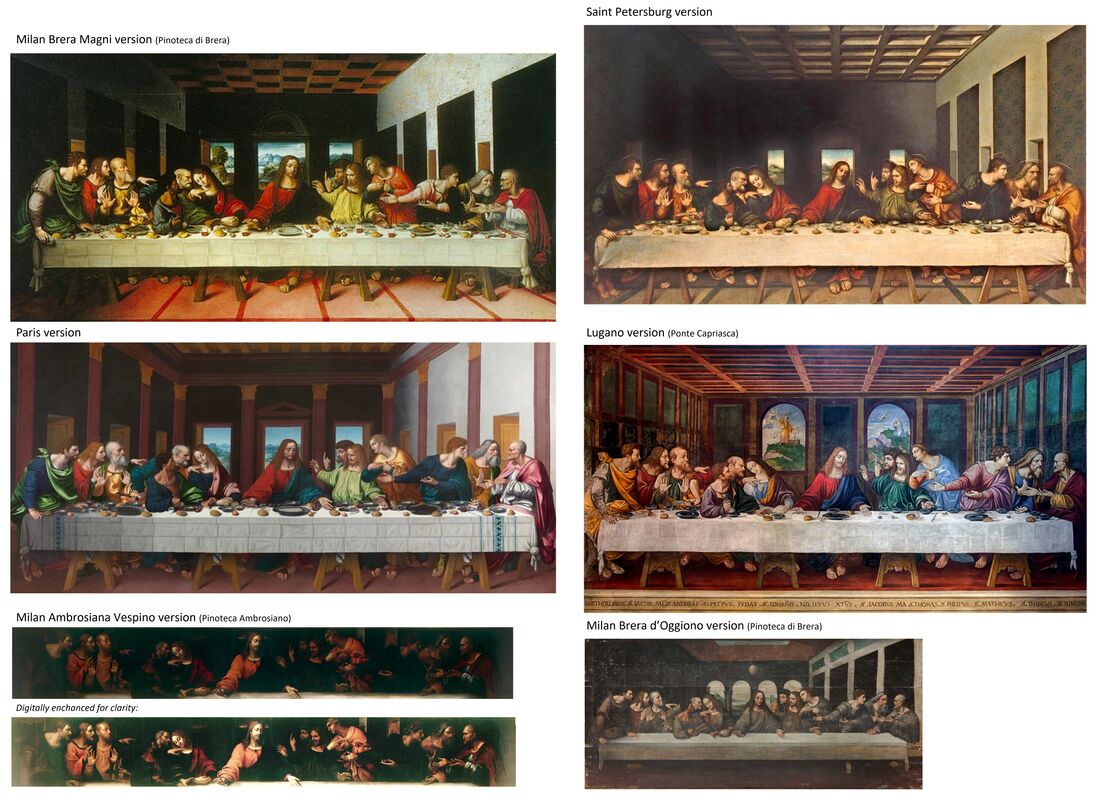

- given the deterioration of the original fresco work and extremes amounts of restoration, one might consider that contemporary canvas copies provide the best experience of what the original must have been, moreover as certain research has shown that canvas copies of the original were made by Leonardo's studio, possibly under his supervision. See Discussion Note 2 that provides an overview of some top 10 famous copies. The best copy known is the Tongerlo version (Belgium), quite close with the London version (UK).

- for the sequence of the apostles, see ao Schema FMC00.021A on Holy Supper symbolism - apostles

- for the 'mystery hand', see Discussion Note 2 below, and Schema FMC00.021E on Holy Supper symbolism - apostles

Illustrations

Original fresco by Leonardo Da Vinci

Schema FMC00.021 shows the current version of the painting after the last restorations (1978-1999)

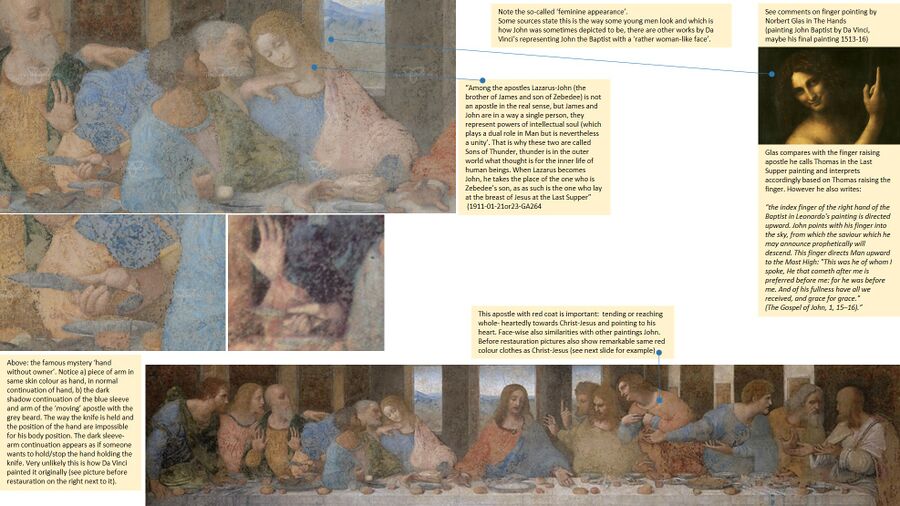

Schema FMC00.021B adds some details with notes, following tentative interpretation in Schema FMC00.0211 on Holy Supper symbolism - apostles

Schema FMC00.021C shows the current painting as well as (right) a comparison with the original after the numerous restorations in the last century.

Best ancient 16th century copies

Schema FMC00.021G: shows the two best historical copies of Da Vinci's Last Supper fresco, that had been deteriorating quickly already decades after it was finished in 1498. These two high quality copies are nearly identical and were originally (nearly) full size canvas versions, that have been used as reference for restauration of the fresco. Studies have shown that these faithful copies were produced in Leonardo's studio by his best students within 20 years of the original, probably under supervision by Leonardo. Research has shown that (with high likelihood), the Tongerlo (Belgium) version was ordered by the King of France directly from Leonardo after seeing the original fresco (see paper by Isbouts and Brown). Its original size (462x828) was nearly exactly that of the fresco (460x880). The London (UK) version was slighly smaller and further reduced in width with the upper part cut (to the current 300x780). Double click further to get high resolution version.

More details in Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci#Note 1 - Copies of Da Vinci's Last Supper.

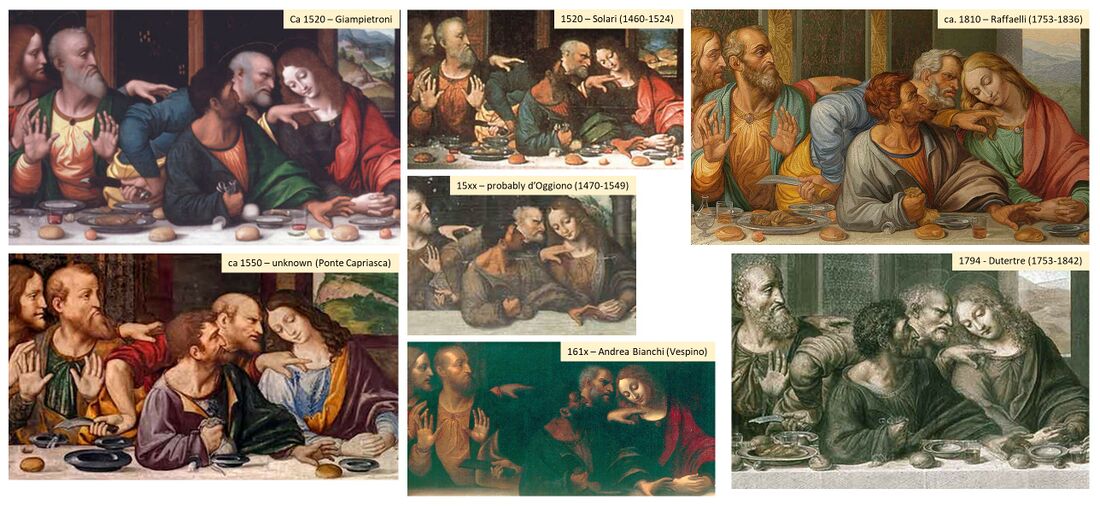

Schema FMC00.021H: gathers a number of the best known copies of the Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci from the early 16th century, all but the Vespino version dating from early 17th century. Note that though these are also famous copies, several of which were also by or attributed to students or followers of Leonardo, the interior architecture and colours are not faithful to the two reference versions and original. Also the sizes vary greatly, some are scaled like two thirds of the original, other are much smaller like 77x132 cm (Saint Petersburg) or 121 × 268 cm (Milan Brera d'Oggiono). The names used here are a combination of the city and museum (abbreviated) where the works are located, in some cases adding the artist as this is how these copies are referenced (Vespino, d'Oggiono). Double click further to get high resolution version.

More information Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci#Note 1 - Copies of Da Vinci's Last Supper

Mystery hand and knife

Schema FMC00.021E compares several versions of the 'mystery hand with the knife' from some of the most well-known reference copies of Da Vinci's painting. For more info, see Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci#Note 1 - Copies of Da Vinci's Last Supper

It illustrates how the 16th century copies show a combination a hand holding the knife and appear to also show a wrist from the vertical arm that connects with that hand. See Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci#Note 2 - The mystery of the hand holding the knife

Careful comparison of copies, considering the full painting, shows many nuances. Note for example the auras above the head on Giampietroni, Peter's vertical arm on the Ponte Capriasci copy, the changes to the colours of the clothing - certain copies keep and others change those colours.

The copies below were taken from maximum resolution copies available in the public domain on the internet. Certain digital copies were adapted to improve clarity of details, eg the Bianchi version is too dark. Click twice to maximize.

Geometries

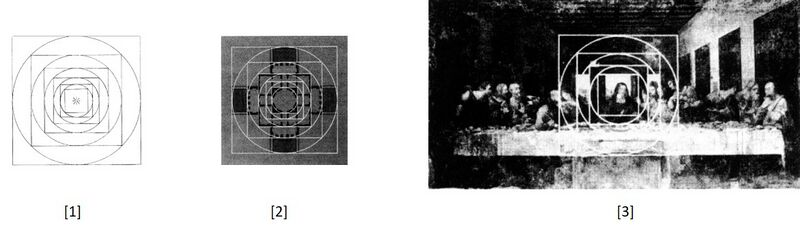

Schema FMC00.021D shows a first example of 'perceived geometries', in this case by Olive Whicher from a study of the etheric with projective geometry and Hans Feddersen, for source and commentary see the Lecture references section.

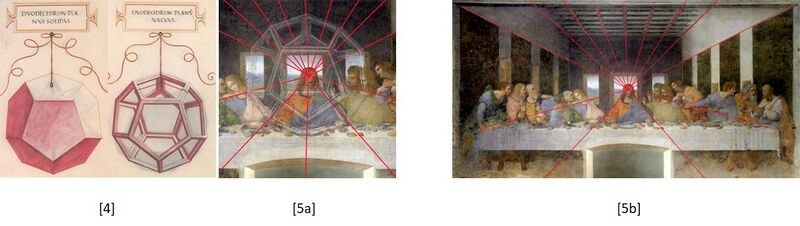

Schema FMC00.021F below is a second example of the many versions of interpretations and patterns that are 'seen into' the Last Supper.

In this case, attention is given to the perspective lines starting from the Christ (no, not 12). Then a dodechedron is presented as the symbol representing 12 times 5 pentagons. The pentagram is the symbol of the human being, whereas Christ is represented with the divine twelve.

Rudolf Steiner used the dodecahedron in the Foundation Stone ritual on 25-Dec-1923.

Many more of such 'perceived geometries' exist, it may be hineininterpretierung, or not. This case is presented because it is far-fetched, so it may well be, most probably, an example of such 'hineininterpretierung'.

Lecture coverage and references

1911-11-14-GA132

.. also covers the symbolism in Last Supper by Da Vinci

And in yet another part of our earth-history do we find this resigning on the part of Higher Beings, and here too we must again refer to something alluded to in the last lecture — the picture of the “Last Supper,” by Leonardo da Vinci.

It represents the scene in which as it were, we have before us the meaning of the earth, the Christ.

While trying to penetrate the whole meaning of the picture, let us recollect those words, which are to be found in the Gospel: “Am I not able to call forth a whole multitude of angels if I wish to avoid the death of sacrifice?” That which Christ might have accepted at that moment, which would of course have been quite easy for Him to do, He rejected in resignation and renunciation.

And the greatest renunciation made by Christ Jesus confronts us when, by having made it, He allows the opponent himself — Judas — to enter His sphere. If we are able to see in Christ Jesus all that is to be seen, we must see in Him an image of those Beings with whom, at a certain stage of evolution, we have just become acquainted, those who must renounce the proffered sacrifice, those whose very nature was resignation. Christ renounced that which would have occurred if He had not allowed Judas to appear as His opponent just as once upon a time, during the Sun-age, the gods themselves called forth their opponents by the renunciation they made.

So we see a repetition of this event in a picture here on earth: that of the Christ seated among the twelve, and Judas, the betrayer, in the centre. In order that that which makes mankind of such immeasurable value might enter into evolution, Christ Himself had to place His opponent in opposition to Him.

This picture makes such a profound impression on us because when we contemplate it, it reminds us of such a great cosmic moment; and when we recall the words: “He who dips his bread into the bowl with me, he it is who shall betray me,” we see an earthly reflection of the opponent of the gods, placed in opposition to them by the gods themselves.

For this reason I have often ventured to say that if an inhabitant of Mars were able to descend to the earth, he might find things which would be of more or less interest to him although he might perhaps not understand them properly; but as soon as he saw this picture by Leonardo da Vinci he would, through a cosmic position which has a connection with Mars just as with the earth, learn something which would teach him the meaning of the earth.

The incident represented in the earthly picture is of significance to the whole Cosmos: the fact that certain powers place themselves in opposition to the immortal Divine powers.

And this representation of Christ surrounded by His Apostles, He who on the earth overcomes death and thus proves the triumph of immortality, is intended to point to that significant universal moment when the gods severed themselves from temporal existence and gained the victory over Time, that is, they became immortal.

When we contemplate the “Last Supper” by Leonardo da Vinci, we may feel this in our hearts.

1913-02-13-GA062

is a lecture dedicated to Leonardo Da Vinci. What the painting depicts is described by Goethe, as referenced in 1913-02-13-GA062:

The name of Leonardo is constantly being brought before the minds of innumerable people through the wide circulation of perhaps the best known of all pictures, the celebrated “Last Supper”. Who does not know Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” and knowing it, does not admire the mighty idea expressed more particularly in this picture? There we see embodied pictorially a significant moment — one that by innumerable souls is considered the most significant of the world's events: the figure of the Christ in the center, and on either side of Him the twelve Disciples. We see these twelve Disciples with deeply expressive movements and bearing; we see the gestures and attitudes of each of the twelve figures so individualized, that we may well receive the impression that every form of the human soul and character binds expression in them. Every way in which a soul would relate itself according to its particular temperament and character, to what the picture expresses, is embodied in them.

In his treatise on the subject of Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper”, Goethe expressed perhaps better than any writer the moment after Jesus Christ uttered the words, “One of you shall betray me”. We see what is taking place in each of these twelve souls, so closely connected with the speaker and who look up to Him so devoutly, after the utterance of these words; we see all that wonderfully expressed by each of these souls in the numerous reproductions of this work which are disseminated through the world.

There have been representations of the “Last Supper” dating from earlier times. We can trace them without going still further back, from Giotto down to Leonardo da Vinci; and we find that Leonardo introduced into his “Last Supper”, what we might call the dramatic element, for it is a wonderfully dramatic moment that confronts us in his representation. The earlier representations appear to be peaceful, expressing, as it were, only the fact of being together. Leonardo's “Last Supper” seems the first to conjure up before us with full dramatic force an expression of very significant psychic conditions.

However in this same lecture:

If we let his “Last Supper” work on us, we find two things of which we can say that they do not altogether agree with Leonardo's view of the principles of painting.

One is the figure of Judas. From the reproductions and also to a certain extent from the shadowy painting in Milan, one gets the impression that Judas is quite covered in shadow — he is quite dark. Now when we study how the light falls from the different sides, and how with regard to the other eleven disciples the lighting conditions are represented in the most wonderful manner in accordance with reality, nothing really explains the darkness on the face of Judas. Art can give us no answer as to the wherefore of this darkness. This is fairly clear as regards the Judas figure.

If we now turn to the Christ Figure, approaching it not according to Spiritual Science but according to the external view, it only produces, as it were, something like a suggestion. Just as little as the blackness, the darkness of the Judas figure seems justifiable, just as little does the “sunniness” of the Christ Figure, standing out as it does from the other figures, seem to be justified, in this sense.

We can understand the lighting of all the other countenances but not that of Judas nor that of Christ Jesus.

Then, as if of itself, the idea comes into one's mind: surely the painter has striven to make evident that in these two opposites, Jesus and Judas, light and darkness proceed not from outside but from within. He probably wished to make us realize that the light on the face of the Christ cannot be explained by the outer conditions of light, and yet we can believe that the Soul behind this Countenance is itself a light force, so that It can shine of Itself, in spite of the lighting conditions. In the same way the impression with respect to Judas, is, that this form itself conjures up a shadow which is not explained by the shadows around it.

This is, as already said, a hypothesis of Spiritual Science, but one that has developed in me in the course of many years and we may believe that, the more we considered the problem, the more we would find it substantiated.

1916-11-01-GA292

We now come to the Last Supper — which he created, it is true, at an earlier time, and worked upon during a long period. We have often spoken of it. We know what an essential progress in the artistic power of expression is visible in this picture as against the earlier pictures of the Last Supper by Ghirlandajo and others. Observe the life in this picture; see how strongly the individual characters come out in spite of the powerful unity of composition. This is the new thing in Leonardo. The adaptation of the strong individual characters to the composition as a whole is truly wonderful. At the same time each of the four groups of disciples becomes a triad complete and self-contained; and, again, each of these triads is marvellously placed into the whole. The colour and lighting are inexpressibly beautiful. I spoke once before of the part of the colouring in this composition. Here we look deep into the mysterious creative powers of Leonardo. If we try to feel the colours of the picture as a whole, we feel they are distributed in such a way as to supplement one another, — not actually as complementary colours, but in a similar way, — so much so that when we look at the whole picture at once, we have pure light — the colours together are pure light. Such is the colouring in this picture.

...

This is Morghan's engraving, from which we gain a more accurate conception of the composition than from the present picture at Milan, which is so largely ruined. You are, of course, familiar with the fate of this picture, of which we have so often spoken.

...

This is a very recent engraving, a reproduction which reveals the most minute study. It is frequently admired and yet, perhaps, for one who loves the original as a work of art, it leads too far afield into a sphere of minute and detailed drawing. Still we may recognise in this an independent artistic achievement of considerable beauty.

[Rudolf Stang, The Last Supper. Engraving after Leonardo, completed in 1887.]

1922-08-27-GA214

It is quite natural to think of one of the most famous paintings that exists and depicts the subject of study here, as indeed this painting is said to contain much more than we see or can understand, as we read in 1922-08-27-GA214

Thus it will be indispensable to turn attention in our time once more to this the greatest question of mankind, inasmuch as the essence and meaning of the whole evolution of the Earth lies in the Mystery of Golgotha. I would fain express it in a parable, however strangely seeming.

Imagine some being descending from another planet to the Earth. Unable to become an earthly man, the being would in all likelihood find the things on Earth quite unintelligible.

Yet it is my deepest conviction, arising from a knowledge of the evolution of the Earth, that such a being — even if he came from distant planets — Mars or Jupiter — would be deeply moved by Leonardo da Vinci's picture of the Last Supper.

For in this picture he would discover that a far deeper meaning lies hidden in the Earth — in earthly evolution. Beginning from this deeper meaning which belongs to the Mystery of Golgotha, the being from a distant world could then begin to understand all other things on Earth.

Olive Whicher and Hans Feddersen

On the cosmic and earthly: the etheric Sun space, see Schema FMC00.021D

Olive Whicher, from a study of the etheric with projective geometry, presents a comparison (see Schema FMC00.021D) between [2] the foundation pattern of the Villa Rotunda in Venise (book 'Rose Windows' by Painten Cowen) and the mathematical ideas from projective geometry, the growth factors due to etheric laws that one also finds in spirals [1]:

if continued inward, the interwoven pattern of squares and circles would leave to what we have called an innermost point at infinity, a centre of ethereal space or Sun space.

and then quotes Hans Feddersen (see figure, right)

The secret of the painting lies in the interpretation of circles and squares, of the cosmic and the earthly. As we eliminate the lines, which have been drawn into the picture, we see them light up again in spirit. If we think about (the circle and square) in the spirit of Leonardo, we know that we are dealing with an invisible figure expressing a deep truth. Through the circle, the spirit of the universe permeates the depths of the earth, whose laws come to expression in the square. It is in the interpretation of earth and heaven that the meaning of the Last Supper is clothed.

Discussion

Note 1 - Copies of Da Vinci's Last Supper

Through the centuries, many copies were made by different artists for different reasons, the main one being the deterioration of the state of the original work. The copies are important in the context of interpretation of certain important elements, such as the 'hand with knife' (Schema FMC00.021E), as the many restaurations over the centuries have affected the current version. Therefore a study of well-conserved early copies probably brings us closer to the original work than the current version.

Note there are many variants of the Last Supper's composition by various artists, also Leonardo's pencil sketches exist but these don't have the final composition (though one carries the names of the apostles).

Below a 'top ten' of the most famous reference copies. For more info, see o.a. wikipedia, cenacolovinciano.org and nicofranz.art/en/leonardo-da-vinci/the-last-supper

From careful comparisons, it's clear that the Tongerlo and London versions are very close to eachother and both present a lively high-quality picture of what Leonardo's original once looked like. In fact it is a recommended exercise to take highres copies of both and compare them carefully.

The Paris and Lugano versions already have another feel, much more of copies less succeeded or faithful. And similarly or even more so this goes for the Pinacoteca di Brera and Vespino versions

See Schema FMC00.021E for an example of a comparison, and commentary Note 2 below.

- 15th century - the original

- approx. 1495-1498: dry wall-painting by Leonardo da Vinci (Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy) - 460 cm × 880 cm

- 16th century - early copies, almost the size of the original, presumed to be work by Leonardo's assistants

- 1/ Tongerlo version

- ca 1520: oil on canvas said to be by Andrea Solari (1460-1524) (now in Leonardo da Vinci Museum of Tongerlo Abbey, Belgium) - 418 by 794 cm

- The article 'A Multidisciplinary Study of the Tongerlo Last Supper and its attribution to Leonardo da Vinci’s Second Milanese studio' by Prof. Jean-Pierre Isbouts and Christopher Brown (downloadable below in Reference section), argues that based on the available evidence, the Tongerlo Last Supper was produced in Leonardo’s Milanese workshop between 1507 and 1509, as a collaborative project involving his students the 'Leonardeschi' Giampietrino, Solario and d’Oggiono under Leonardo’s supervision. Infrared spectography scans suggest that the face of John in the painting may have been painted by Leonardo himself.

- documented provenance goes back to 1545

- reduced by some 34 cm of width and 44cm of height

- 2/ London version

- said to be by Giampietrino (active active 1495–1549) [and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (1467 - 1516)] ca 1515-1520 (now in collection Royal Academy of Arts, London) - canvas 302 cm x 785 cm, or 298 x 770 cm

- In 2017, after 25 years at Magdalen College in Oxford, this painting was returned to the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

- it is also known as the Certosa copy, or 'Certosa di Pavia', the name of the monastery where it was kept originally before it was acquired by the Royal Academy of Arts in 1821

- full-scale copy that was the main source for the twenty-year restoration of the original (1978-1998). It includes several lost details such as Christ's feet, the transparent glass decanters on the table, and the floral motifs of the tapestries that decorate the room's interior. First mentioned in 1626 by author Bartolomeo Sanese as hanging in the Certosa di Pavia monastery in Italy. At some point, the upper part was cut off and the width was reduced, so it is much reduced in height.

- 3/ Paris version

- copy by Marco d’Oggiono (1470-1549) known as the Ecouen copy, depending on source ca 1506-1509 or 1524-1530 (Musee National de la Renaissance, Château Écouen, near Paris, France). d’Oggiono was a chief pupil of Leonardo da Vinci and copied many of his works. Scaled approx 2/3 of original.

- interior architecture has been greatly altered

- Lugano version

- by Cesare da Sesto (1477-1523) [or unknown artis, depending on source] (in Church of Sant' Ambrogio in Ponte Capriasca near Lugano, Switzerland) - 302 mm x 785 mm

- this is the earliest copy known that includes the names of the apostles beneath each of the figures, still used today

- Milan Brera Magni version

- by Cesare Magni, Pinacoteca Di Brera, Milano (IT),

- Note, in the same location, also another copy of early 16th century: canvas copy believed to be painted by Marco d’Oggiono (1470-1549) (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan) - only 121 × 268 cm; however this is really not a very good copy in terms of colours or expression of the faces

- Saint-Petersburg version

- early 16th century, State Hermitage museum, faithful copy but only 77x132 см

- 1/ Tongerlo version

- 17th century

- 1612: the original work by Da Vinci was severely damaged.

- Milan Ambrosiano Vespino version

- 1611-1616: Andrea Bianchi also known as 'il Vespino', (commissoned by Cardinal Borromeo to produce a copy of it on canvas, so that there would at least be some evidence of the painting’s condition. (Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milano). A rather dark and not so magnificent copy compared to others.

- 18th and 19th century

- 1794 - André Dutertre (1753-1842) (commissoned by Louis XVI of France) carried out a very in-depth study of the painting and other copies that had already been made, to produce the best replica of the Last Supper,

- 1807-1809: Giuseppe Bossi made a copy of the painting in original size. The painting was destroyed during the air raids of 1943. but traces remain in preparatory tracing works held in Weimar and a mosaic replica by Giacomo Raffaelli

- 1806-1814: mosaic replica by Giacomo Raffaelli (1753-1836) (now in the Minoritenkirche, Vienna)

Note: Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519) his direct circle and following included:

- Andrea Solari (1460-1524) - follower of Leonardo

- Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (1467 - 1516) - worked in Leonardo's studio

- Marco d’Oggiono (1470-1549) - close pupil in Leonardo's studio

- Giampietrino - probably Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, active active 1495–1549) - Leonardo's circle

- Cesare Magni or Magno (ca.1495–1534)

Note 2 - The mystery of the hand holding the knife

Introduction

A lot has been written about 'The Disembodied Hand' in Da Vinci's Last Supper painting, especially since the novel by Dan Brown, 'The Da Vinci Code' (2003) became a bestseller worldwide. In the novel, the 'spare' hand is described as "disembodied. anonymous", and the character notes, "if you count the arms, you'll see that this hand belongs to ... no one at all."

On the left of Christ-Jesus, we find John (with a said feminine appearance), Judas (seated, holding a purse), and Peter (standing and angry). One of Peter's hands is on John's shoulder while the other is likely to be the one called the disembodied hand, directly below his hip with the blade pointed to the left. The image is confusing to the eye, as Peter's arm appears to be twisted and his shoulder and elbow seem to be at odds with the angle of the hand holding the dagger.

Peter, in later scene, wants to defend Christ-Jesus with a knife as the guards come to take Christ-Jesus away. Many people interpret that the fact that the knife points out of Judas' back is also why the apostle on the left has his hands up from the surprise and danger.

Given Leonardo's brilliant mastery of human anatomy and physiology, and the fact he worked for about three to four years on the painting, it is impossible that this is an amateuristic oddity of sorts, rather it rightly points to a mystery and some hidden message that was very consciously put into the painting in a symbolic form. The detail is the more remarkable given the fact this has become one of the most famous paintings worldwide, and Leonardo 'got away' with deliberately but subtly having a floating hand on the painting.

For detail on the original, see Schema FMC00.021B. For a comparison of the detail on the most important copies of Da Vinci's work, see Schema FMC00.021E.

Positioning facts and fiction

Lots of speculation can be found in literature on the internet on this 'mystery hand'. Forums with many hundreds opinions and the wildest fantasies can be found. For example, the American writer Lisa Shea wrote about this in an online article 'The Mysterious Hand and Knife' and this triggered so many responses that a separate forum page was created in 2004, which has about fifty pages of reactions and opinions until today, see forum on 'The Hand and The Knife'.

As further reading, we present below a rare but well documented paper from the art historian Diego Cuoghi which homes on this question andtries to de-mystify this in a sound rational way.

> Diego Cuoghi: 'Mystery hand and knife in Leonardo's Last Supper' (PDF paper - machine translation from Italian website page)

Commentary

The page Holy Supper symbolism - apostles provides the documentation on how Rudolf Steiner linked the apostles symbolically to the cultural ages.

If we see John as the representative of the fourth cultural age (not counting Christ-Jesus as Christ is an external divine impulse that is not part of this sequence), then Judas rightly becomes the representative of the evil or betrayal of the Christ Impulse in the fifth age. Steiner describes this betrayal as mankind's "snake bites the lion [Christ] in the heel" (see FMC00.373A)

The sixth cultural age is the one where the Christ Impulse blossoms, and that will provide the basis for the great next Sixth epoch.

Projecting this information into this context, makes Peter's move from his normal position representing the sixth, towards John as Christ's representative on Earth in terms of teaching and impulse, an interesting topic for contemplation. Peter has a hand on John's shoulder, he makes the connection. But what could be the meaning of this shift in the position, the first oddity, and also the hand and knife in that position, the second oddity?

Further speculation

Hereby a few hinein-interpretiering speculative thoughts, in case we want to adhere to what is presented in Schema FMC00.021A as making sense, which on itself is already a pure hypothesis. If we go by this Schema and its proposed logic, can we find any meaning in Peter with the knife?

First a consideration upfront. Peter is the only one who looks angry, carries a knife, also the later representative of the church (that would become the Roman Catholic Church, also a kind of betrayal of the authentic Christianity as an institution). Is it not a strange casting for the sixth cultural age representative?

1) A first thought-scenario, and an impossible or most unlikely one. Peter shifts to cultural age position 5 and Judas 6. Debatable because he doesn't with his body. Still, in that case the real betrayal in the fifth cultural age would come from the Peter, and Judas would be a representative of the sixth age. This is not consistent with Judas betraying Christ-Jesus, and Steiner also describing Judas as the representative of that fifth age of betrayal.

2) The knife is a symbol, for example of great upheaval between the fifth and sixth ages, which will definitely be the case, and Rudolf Steiner mentioned it very explicitly. One could also see the knife as the two-edged sword, the human 'I'.

Note however that there also great upheavals between the epochs, and these don't appear represented on the painting. On the right indeed the first three apostles are separate from the next, maybe pointing to the transition between fourth and fifth epochs. But on the left that is not the case.

3) Peter is actually 'over' Judas, it is as if he wants to rush for Christ-Jesus, and so he is both with John as on his sixth age position. One might interpret he is 'bridging'. This does provide an explanation for the knife, it's position and the hand holding it maybe in a strange way.

Notes:

1/ On the side: it is interesting to note that the apostle representing the first age of the sixth epoch also reaches out and touches Peter's back with his hand, again - one could say - consistent with the sequence as proposed on Schema FMC00.021A above.

2/ The knife is at the height, just in front, of the apostle representing the seventh cultural age, but he looks at Christ-Jesus, not at the knife (except maybe on the Solari version). In fact nobody looks at the knife at all.

2/ Also, the apostle identified as Judas not only holds the purse, he is the only one who grabs for the bread, and is also seen pushing over the salt.

Matthew 5:13: You are the salt of the earth, but if the salt has lost its flavor, with what will it be salted? It is then good for nothing, but to be cast out and trodden under the feet of men. Luke 22:19: And He took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, “This is My body which is given for you; do this in remembrance of Me".

This has to be put in context, as the painting depicts the moment that Jesus predicts his betrayal during the during the Last Supper, see also Matthew 26:24–25, Mark 14:18–21, Luke 22:21–23, and John 13:21–30. And after saying he will betrayed he is asked who will betray him, and:

John 13:25-26: So that disciple, leaning back against Jesus, said to him, “Lord, who is it?” Jesus answered, “It is he to whom I will give this morsel of bread when I have dipped it.” So when he had dipped the morsel, he gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot.

So this might be why we see Christ-Jesus' hand open, from passing on the bread, and Judas' hand as well, in the process of taking the bread.

Related Pages

References and further reading

- Johannes Kühn: 'Leonardo da Vinci : Die Darstellung des Abendmahls im Wandel der Zeiten' (1948)

- Hans Feddersen: 'Leonardo da Vinci's Abendmahl' (1975)

- Wilhelm Pelikan: 'Lebensbegegnung mit Leonardos Abendmahl' (1988)

- Willy Finkenrath: 'Das Zeugnis des Wortes - das Abendmahl des Lionardo Da Vinci' (2003, in short in Novalis 4 of 1998)

- Michael Ladwein: 'Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper: A Cosmic Drama and an Act of Redemption' (2006 in EN, 2004 in DE as: 'Leonardo Das Abendmahl - Weltendrama und Erlösungstat')

- Adrian Anderson: 'Rudolf Steiner on Leonardo's Last Supper: The Connection of Jesus, the Cosmic Christ, and the 12 Disciples, to the Zodiac' (2017)

Papers

- Thomas Meyer: Leonardo da Vincis Abendmahl und die Auseinandersetzung mit dem Bösen (Der Europaër, Apr 2002, article in PDF paper)

- Prof. Jean-Pierre Isbouts and Christopher Brown: 'A Multidisciplinary Study of the Tongerlo Last Supper and its attribution to Leonardo da Vinci’s Second Milanese studio' (PDF paper)

- Diego Cuoghi: 'Mystery hand and knife in Leonardo's Last Supper' (PDF paper - machine translation from Italian website page)